Welcome to my 11th newsletter. There is only one story to tell this quarter so I hope you will forgive me.

I have to admit that when I received an email on Sunday 3 June at 11:08 with the subject ‘Invitation to private audience with the Dalai Lama, London, 20 June. The British in Tibet’, I did not take it seriously. In fact, I ignored it. I was about to consign it to my Junk E-mail box when I saw the postscript at the bottom of this relatively brief email: the name of someone I knew well, which made me look again. On reading the email properly I realised that it was a genuine invitation and it was meant for me . . . and 59 others. Sandy Irvine in Tibet on the first day of the trek across the plateau.

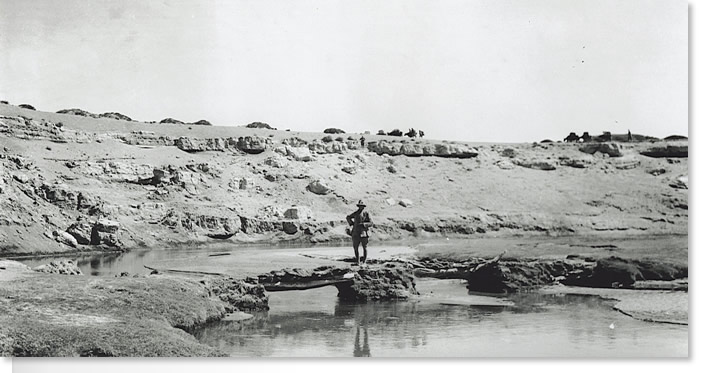

Sandy Irvine in Tibet on the first day of the trek across the plateau.

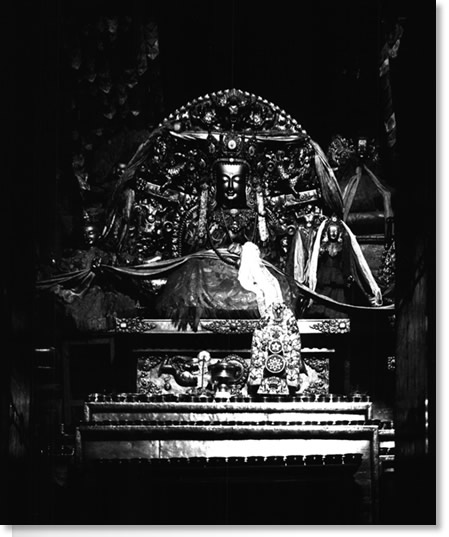

The Dalai Lama immediately recognised this as Western Tibet. Sandy’s photograph of the interior of the Holy of Holies at Shekar Dzong, destroyed during the 1950s.

Sandy’s photograph of the interior of the Holy of Holies at Shekar Dzong, destroyed during the 1950s. This photograph was taken by Captain John Noel at Shekar Dzong.

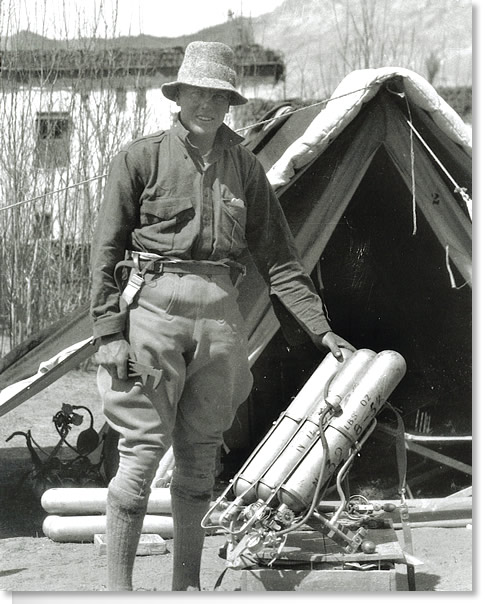

This photograph was taken by Captain John Noel at Shekar Dzong.

Sandy is holding up the Mark V oxygen apparatus.

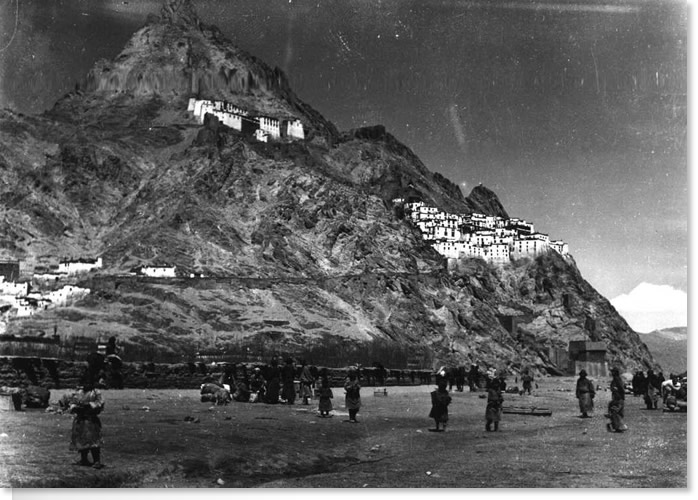

© Sandra Noel (not to be published without written permission of Sandra Noel) Sandy took this photograph of Shekar Dzong when the expedition spent a night there in April 1924.

Sandy took this photograph of Shekar Dzong when the expedition spent a night there in April 1924.

He, Norton and Mallory tested his Mark V oxygen apparatus on the rocks below the Dzong.

The Dalai Lama was fascinated by this picture and kept scrutinising it.

His Holiness was undertaking a 10-day tour of the UK, and it had been suggested that in London he might like to meet members of families whose relatives had been in Tibet prior to 1950. Apparently this was something he had done before, and this time the organiser, Roger Croston, had decided to invite members of the families of the 1920s Mount Everest expeditions. So, on the appointed day at the appointed time – 10am – Julia Irvine, son Simon and I met outside the Dean’s gate at Westminster Abbey and were duly shown through the fabulous medieval complex of buildings, past the dining room where Julia’s son, Alexander, has dinner (he’s at Westminster School) and into a lobby that led into a suite of rooms that ended in the Jerusalem Chamber, which is not open to the public. Simon and I were dressed in scruffy clothes as I did not want to travel in my cream skirt and silk jacket and Simon did not have a suit in London. We managed to get changed into our finery and joined Julia in the magnificent, historic chamber.

The Jerusalem Chamber is probably best described as super-domestic scale, in that it is intimate but there is plenty of room for a good crowd of sixty to seventy. The walls are decorated with magnificent tapestries and the ceiling, we were informed by the Dean who welcomed us, is original, i.e. 14th century. As this was my period in architectural history I was very excited to be in such a beautiful and important part of the Abbey complex. Someone whispered in Julia’s ear that Henry III had died in front of the fire while warming himself but the Dean corrected that and told us that Henry IV had died in the chamber. My great friend Graham Ives, who is the best informed person on the architectural and general history of London that I know, filled in the details. In 1413 Henry IV was planning to go to the Holy Land but when praying at St Edward’s Shrine in the Abbey he suffered one of his frequent blackouts, akin to an epileptic fit, thought to have been caused by kidney disease. He was brought to the Abbot’s house and laid by the fire where he recovered consciousness. The King asked where he was and was told ‘Jerusalem’. It had been prophesied that he would die in Jerusalem and so now that he was ‘there’ he could die in peace, which he did.

The crowd that had gathered for the audience was a mixture of Everest families and others whose relatives had been in Tibet. I was particularly pleased to meet two great-nephews of one Charles “Bunny” Searle, who was a doctor in Tibet in 1940. He had been a rower and had been coached by the greatest of coaches of all time, Steve Fairbairn, at Jesus College, Cambridge in the 1920s. Fairbairn used to criticise him for shunting forward with his bottom. Long after Serle had left Jesus he was sculling on the Thames near Putney, minding his own business when he heard a booming voice: ‘Stop shunting!’ He knew immediately who this was. Great coaches never forget their rowers and their idiosyncrasies.

Another very exciting meeting for us was with Christopher Norton, whose grandfather led the 1924 Mount Everest expedition. He produced photographs of sketches done by his grandfather of the expedition members and we saw, for the first time, a lovely caricature of Sandy Irvine. It was a good thing we had all this fascinating history to think about as we had over an hour and a half to wait for His Holiness.

Eventually, ten minutes later than billed, His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, walked into the room. There was an audible gasp and then applause broke out. He beamed and made straight for the nearest person to him and shook him warmly by the hand, only to be grabbed by the Dean’s minder and ushered behind a podium in front of the fireplace. He seemed amused by the protocol. There were to be speeches first, he was told. He laughed, which made us all laugh and relax. Clearly, organising an audience with the Dalai Lama is a great deal more difficult than with, say, a member of the royal household, as he likes to do his own thing. The Dean gave a short welcoming speech, alluding to the long and distinguished history of the chamber. Then a man called Giles Ford, whose father Robert had been asked to give a short welcome by his friend, the Dalai Lama, but who was indisposed due to a bad cold, stood up to read out his father’s message. [Robert Ford worked as a radio operator in Tibet from 1945-50 when he was captured on the border by the invading Chinese army. He spent five years as a prisoner and wrote a book called ‘Captured in Tibet’.] During this speech the Dalai Lama noticed a little boy in the audience the great grandson of Captain Thornburgh, who was one of the four British (and the only Westerners ever), who were present at the enthronement of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa in 1940 . He had seen him when he walked into the room and had nodded and waved to him, but now he indicated to an aide that he wanted his bag – a sort of sack in the deep red of his robes. Smiling all the while and looking around the room, and nodding encouragingly at Giles, he delved into the bag with his left hand and produced a sweet which he took over to the little boy and, kneeling before him, offered it on his outstretched hand. It was enchanting and everyone relaxed just a little bit more.

Then he spoke. He talked about the value of democracy and how it was possible to have a figurehead and a democracy, citing the Queen as head of state. He spoke about Tibet and how it had been savaged by the Chinese, but he also mentioned our own dodgy past with reference to the mission to Lhasa before the First World War. Then, he said, the soldiers had shown restraint and only used force where necessary. Later the Chinese were indiscriminate and brutal and undisciplined. Hard-hitting stuff but he had an unquestioning audience. Commonsense and compassion would always win over the gun, he claimed. He said that his experience showed that the Chinese political leaders had lost that part of their brains where commonsense is usually housed. ‘I told Obama,’ he said, grinning as we applauded his spectacular name drop, ‘I told President Obama to bring some commonsense to the Chinese.’ He concluded by asking us to keep the history of his country alive but not to be starry-eyed about it. Not everything prior to 1950 had been as perfect as often painted, nor is everything as bad as critics of the current status quo would have everyone believe. It was a strong message and whether you believe in it or not, he is compelling to listen to on the subject.

Next up we had our moment of glory, which was really special. The crowd had been divided into groups of 12 based on the dates when their relatives had been in Tibet. The Irvines (and Mallorys, Moresheads, Noels, Odells and Bruces) were in group C so we got an early slot. Simon, Julia and I were pushed forward to shake his hand and to show him photographs of Sandy in Tibet which we had taken with us. I had chosen a photograph taken by Sandy in the temple of the Holy of Holies at Shekar Dzong, an important monastery about a day’s walk from Everest base camp, which was destroyed in the 1950s. The Dalai Lama was fascinated by the image and pointed to the temple and then the photograph of the great Buddha with real enthusiasm. He grabbed Julia’s hand and held my arm while we had our photographs taken. Simon reckoned we had over a minute with him. I don’t know as it felt somehow timeless. After that others had their turn and we could stand back and enjoy their pleasure. At one stage he met an old lady the daughter of the botanist, Francis Kingdon-Ward, who had explored Tibet. She was tiny – about 4’5″ – and he bent down and touched her forehead with his in a most passionate gesture. It quite took my breath away. We never did learn why he was late but we were very happy that he spent over 40 minutes with us rather than the scheduled 15.

So, what was he like? It is hard to describe him without resorting to clichés. He is every bit as impressive as you would expect but the two things that struck me most strongly were his force of inner life and his constant movement. He was never still, not for one second. If it had been a child or another person you might have said he was fidgeting but it was not that at all. It was as if a powerful, inner energy was bursting to get out and it manifested itself in his perpetual but very graceful motion, sometimes in large gestures, often in small. That is what I will take away from our audience with the 14th Dalai Lama, that inner energy and that remarkable strength.

There is no room for any more in this newsletter and, indeed, how would I follow that life-changing experience? Rather than look forward I am happy (unusually) to enjoy the moment.

Julie Summers

June 2012, Oxford