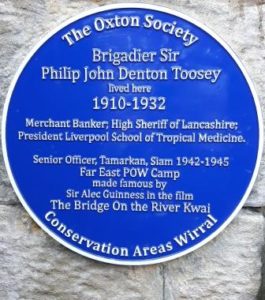

This is t he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

Brigadier Sir Philip John Denton Toosey was born in Upton Road in 1904 and moved to 20 Rosemount in 1910. Over the course of his life he played a role in the lives of many, many people from all walks of life: from Liverpool to Lima, from Barings Bank to the Bridge on the River Kwai and from Oxton to Africa. He had the ability to make you feel as if you were the only person who mattered at that moment in time, whether you were being praised on parade, being given a severe rocket for leaving bicycles on a train or drawing on the dining room wall paper. Latterly people felt his gaze upon them as he fundraised energetically for the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.

To one man, however, he was a figure of such significance that he changed the course of this man’s life. Sergeant Major Teruo Saito was second in command at Tamarkan in Thailand when Colonel Toosey and his men marched into the bridge camp on the River Kwai to the tune of Colonel Bogey. Saito was a regular army officer from the Imperial Japanese Army and although his methods of discipline were brutal, Toosey always argued that Saito knew how to handle men and there formed an unlikely bond between the two of them based on mutual respect. Toosey wrung concessions out of Saito for his men, such as rest or Yasume days, a canteen and the right to discipline his own men rather than leave it to the Japanese. In return he agreed to keep the camp clean and morale high, which in itself saved hundreds of lives. In 1943 Toosey was involved in a plot to help two officers and seven soldiers escape. The men were all captured and executed. Toosey told Saito that only he had known of the plan and as such he was subjected to a severe beating and was forced to stand to attention for twenty-four hours in the tropical heat – a humiliation initiated by Saito as a way to show the Kempi Tai (the Japanese equivalent of the Gestapo) that he had dealt with the situation. Saito’s actions undoubtedly saved Toosey from an even more unpleasant fate.

At the end of the war when Toosey was asked to help screen the Japanese and Korean guards for war crimes he told the investigators that Saito should be set free. This made an enormous impression on the Japanese. In 1974 he wrote to Toosey:

For long period of time I have been harbouring the wish to meet you and express my thanks to you. I especially remember in 1945 when the war ended and when our situations were completely reversed. I was gravely shocked and delighted when you came to shake me by the hand as only day before you were prisoner. You exchanged friendly words with me and I discovered what a great man you were. Even after winning you were not arrogant or proud. You are the type of man who is a real bridge over the battlefield.

A decade later, in what would have been Toosey’s 80th year, Saito came to Britain at the invitation of Professor Peter Davies, Toosey’s first biographer. They visited the grave in Landican cemetery and Saito expressed surprise that there was no great monument but a simple headstone.

He asked to spend a few moments at the grave as to say a prayer, for he had converted to Christianity after the war. Later that afternoon he came here to tea with Patrick and Monica and saw 20 Rosemount. He returned to Thailand and wrote to Peter and Patrick:

I feel very fine because I finish my own strong duty. One thing I regret, I could not visit Mr Philip Toosey when he was alive. He showed me what a human being should be. He changed the philosophy of my life.