If you savour the concept of a British village in the middle of the twentieth century it is all too easy to think of a chocolate-box scene with cottages and houses surrounding a duckpond with a postman cycling by whistling while a farmer drives his sheep to market. So it may come as some surprise to learn that thousands of villages were surrounded by camps occupied by foreign servicemen and women, governments-in-exile and refugees from continental Europe. The majority of the visitors had never been to Britain before and fewer still had set foot in an English village.

In 1944 over a million more American GIs arrived to prepare for the invasion of Europe. Few of them had left America before and by the time they arrived in unfamiliar Britain they had suffered a debilitating troopship crossing of the Atlantic in their convoys, dodging submarines, landing in Northern Ireland before being billeted who only knew where. They were put up in remote country villages where no restaurant had even heard of – let alone served – a hamburger. The lack of showers, central heating and lager led many to feel homesick initially, but some grew to love the pretty countryside and the quirky English ways.

By and large they were welcome guests and had a good reputation among local communities for putting things right if they went wrong. A schoolboy in Dorset said that a neighbour had been delighted when his farm, damaged by American tanks on manoeuvres, was restored within a week. They repaired all the hedges and even helped out with the harvest, towing the old- fashioned binding machines with their jeeps. Another group damaged an ancient gateway leading to a fine manor house but restored it to its former glory in two days. The owners of Peover Hall in Cheshire were not so enthusiastic as the farmer in Devon. The US Third Army was based there and General Patton had his headquarters in the large Georgian wing in the build- up to D- Day. In 1944 a fire was started by a soldier and the house was so badly damaged that the wing was demolished after the war and the house returned to its pre-Georgian dimensions.

The arrival of Americans in such vast numbers had a major impact on life in certain areas of Britain. The fishing village of Fowey in Cornwall had the magnificently named USN AATS B, or the United States Naval Advanced Amphibious Training Sub Base, which trained at Pentewan Beach twelve miles to the west. The officers were billeted at Heligan House and 850 men lived in tents. It was said that in the build- up to D- Day it was possible to walk across the river from Fowey to Polruan on American boats and landing craft, a distance of over 400 metres at high tide. Soldiers charged around the tiny narrow lanes in convoys of jeeps, while the village halls shook to jitter- bugging and children crowded around for sweets and chewing gum, which the Americans seemed to have in unlimited quantities. The citizens of Fowey quickly became used to their new guests with their enthusiasm and energetic attitude towards life. Then one day they woke to find the harbour empty and the Americans gone. They, like all the other GIs spread across the south-west, had left the shores for the beaches of Normandy.

The US 333rd Field Artillery Battalion (FAB) arrived in Britain in February 1944 in preparation for the Ardennes offensive, or the Battle of the Bulge. The soldiers were a black battalion from Alabama, a small number of the 130,000 black soldiers billeted in Britain from 1942 onwards. For many inhabitants of the small Cheshire village of Tattenhall, where the US 333rd FAB were housed, it was the first time they had encountered a black man. Equally, the Cheshire countryside provided a novelty for the southern American soldiers: it was the first time they had ever seen snow. They were billeted in and around a house called the Rookery, hunkered under the commanding ruin of Beeston Castle which is situated on a magnificent rock towering over the Cheshire plain and leading the eye westward to north Wales.

Alabama in 1944 was still a segregated state and the soldiers had to be reassured that it was permissible for them to walk on pavements or go into the same pubs, shops and restaurants as their British hosts. When the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion left Tattenhall in summer sunshine six months after they had arrived in snow, one of the soldiers, Private George Davis, wrote, ‘We have found Paradise’. Tragically, many of the soldiers never returned to Alabama. Some were killed or captured near Antwerp but Davis was one of eleven soldiers who became separated from the rest and was hidden by a sympathetic Dutch farmer, only to be betrayed by a Nazi sympathiser and brutally murdered by the Germans at Wereth.

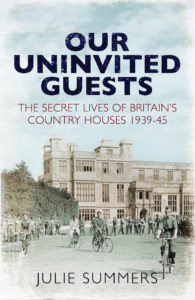

The British countryside opened its heart to the incoming soldiers but nothing could protect them from the brutality of war. Their stories feature in the final chapter of Our Uninvited Guests.

Wonderful article portraying a side of British-American relations I had never read.

This is great reading, thank you.