This is the eulogy I gave for my father, Peter, at the Service of Thanksgiving we held for him in St Mary’s Church at Acton on 3 March 2022. I do not normally write about my immediate family but several people have asked me for a copy of the words I spoke so I thought I’d break a habit. My father lived a long life spanning ten decades. I remember him saying to me in 1999 ‘good gracious, I never imagined I would make the millennium.’ Well, he did. And another twenty years at that.

I’d like to stand up and talk about Daddy for two hours, but you’ll be glad to know that I will rein myself in and speak for just a few minutes.

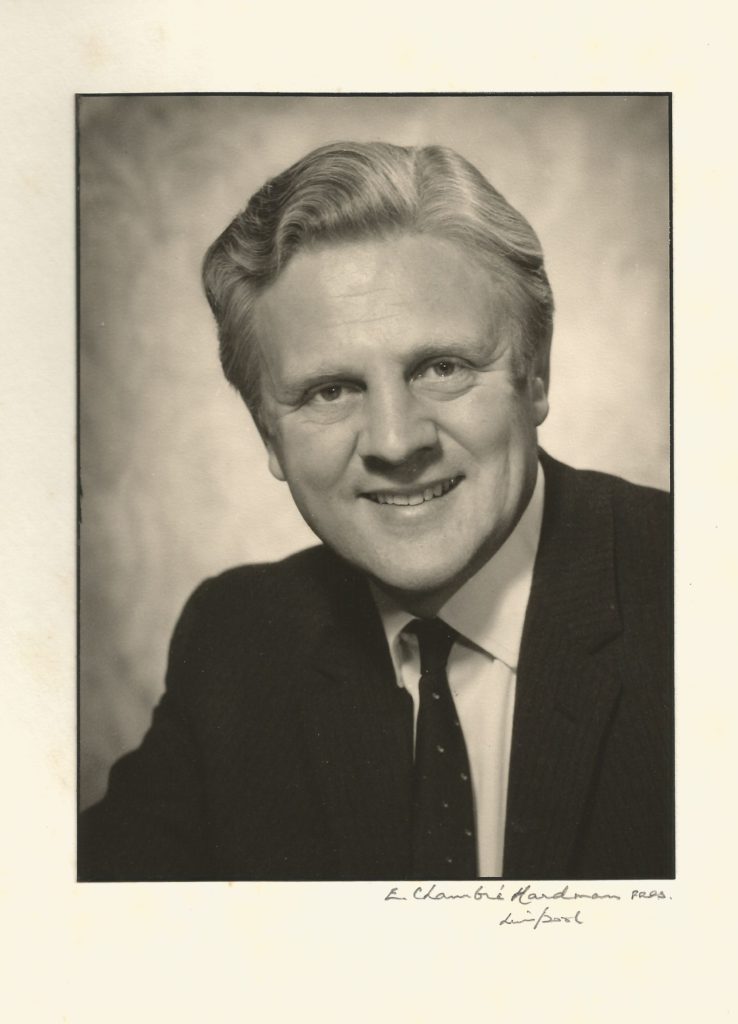

Peter John Summers was born at Denna Hall at Burton on 6th May 1929. Over the next ten decades he acquired many more names: Pete, PJ, Daddy, Uncle Peter, FIL (Father-in Law), Grandpa, Great Grandpa. He also had any number of nicknames: Uncle Speeds, the Fat Controller and the Square Squire are just three of them. It is said that a person with many names is someone who is much loved. That is certainly the case with Peter. The messages of condolence we as a family have received over the last fortnight have been beautiful and heart-warming. Words like distinguished and gentleman keep cropping up.

Peter was indeed a gentle man. Throughout his life he eschewed conflict, but he was never afraid to stand his ground when he knew he was right. He did this in his own inimitable way, quite often with a deliberate, silent stare. It could be remarkably effective.

Peter was educated at home by a governess with boys from other local families, including the Behrends, Glazebrooks, Leaches, and Robin Higgin, until it was time to go to the Leas School at Hoylake. From the autumn term of 1939 the school was relocated to Glenridding on the southern tip of Ullswater in the Lake District. There he spent a happy year sharing a room above the post office with his life-long friend, Bill Glazebrook. From Glenridding he went to Shrewsbury School, following in the footsteps of his father and his mother’s five brothers.

After Shrewsbury he moved into National Service, joining the Signals, and spending three cold months in the autumn of 1947 at Catterick. As a young subaltern he was posted to Vienna for a year, living in barracks in the magnificent Gloriette at Schönbrunn Palace. This was the Vienna as depicted in the film the Third Man, made that same year – a city damaged beyond recognition by bombing, divided into four sectors, where the Black Market thrived, and Americans raced around in jeeps. Peter took it all in his stride and was enchanted by the people. He learned to speak German while playing chess with friends he made there. One of them, Geoff Schiffmann, had been a prisoner of war in the Lake District when Peter was at Glenridding as a schoolboy. He remained in touch with Geoff and Etti Schiffmann for the rest of their lives. He encountered Russian soldiers in Vienna and with his brilliant ear for languages, picked that up too. On returning to Britain, he took up his place at Clare College Cambridge, to study Russian and German.

Peter always had a strong pastoral side to his character. Now, with a degree and National Service behind him he told his tutor at Clare he wanted to work with refugees. He was persuaded against this and encouraged to join the family firm. His godfather, Neville Rollason, was sure there would be room for Peter’s youthful ideals and ambitions at The Works. One of the first roles he was given was to draw up a refuse disposal project. This would be the fastest way to learn about the people and purpose of every department in the company.

He joined the board of John Summers and Sons in 1960 with responsibility for staff training and communications. Seven years later the government nationalised the steel industry and Peter joined the new board of the Scottish and Northwest Group of the British Steel Corporation as Director of Personnel and Social Policy. At that time, he had a secretary called Bridget Johnson who we children all delighted in hearing say on the phone in the crispest of tones: ‘This is Bridget Johnson, your father’s secretary. Is your mother in, please?’ In 1973 the government announced it would phase out iron and steel making at Shotton. This ended eighty years of Summers’ family history but not Peter’s. He was given responsibility to assist some of the 6,500 people who would lose their jobs as a result. Thus started the second and most rewarding part of his business career.

As the Industry Coordinator for the Northwest, he moved into a new office, a little bungalow called Park House in Shotwick. From there he and his tiny team encouraged other industries to move to Deeside. My mother, Gillian, used to provide lunches for the Park House brigade and on one occasion had made a delicious coronation chicken. Peter’s PA, Felicity, asked him whether it was from Gillian’s own hens. He replied, ‘yes, this one was called Fred. I remember him well. He had a slight limp’. Peter claimed that Felicity became vegetarian thereafter.

He said of his work at Park House: ‘My job with BS Industry evolved continuously and provided me with some of the most rewarding experiences of my working life. Starting a small business from cold in an isolated bungalow spurred on by murmurings of polite disapproval, was an experience I wouldn’t have missed for anything.’ His first signing was Iceland Food and he received a frozen lobster every Christmas from then until he left Park House. For this work and the creation of over 4,400 jobs in 87 new factories, Peter was awarded the MBE. He retired in 1989 at the age of sixty.

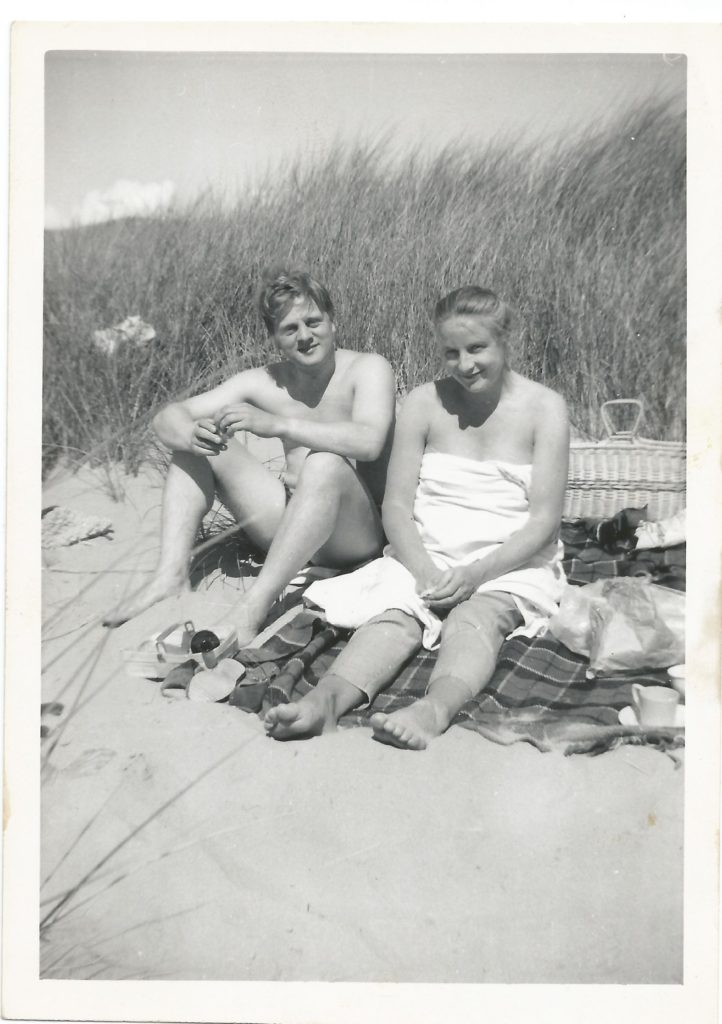

What of Peter the family man? In 1957 he met Gillian Toosey, the daughter, as it happened, of a member of his mother’s tennis group in the early years of the century. They made a very handsome couple. With remarkable speed – almost certainly urged on by Gillian – the engagement was announced, and they married on a windy day in April 1958 to much rejoicing. A honeymoon to the South West of the UK and then the continent in Peter’s TR4 followed. He owned every model of the TR series over the course of almost thirty years. We all remember his love of his sports cars.

Four children followed between 1960 and 1967 – Julie (that’s me), Stephanie, Jeremy and Tim. Life at Delamere Manor, where he moved the family to in 1967, was busy, noisy and unbelievably cold. In 1973 came the oil crisis. The price of oil rose by 300 per cent and Peter turned off the central heating. He did not turn it on again for 45 years.

As children we were fascinated by his various rituals. One was the morning cold bath which he had every day of his life until he retired. Jeremy coined the phrase ‘One, Two, Three Wubbage!’ as Peter hopped into the bath and braced himself for a quick lie down. Another was his breakfast boiled egg which he enjoyed six days a week, latterly seven, until the last week of his life. He timed his egg to perfection on his watch and then solemnly removed it from the pan, ran it under a cold tap, popped it into a yellow egg cup and removed the top with what he called his Ei-Knipps. That, accompanied by toast and Gillian’s delicious marmalade, set him up for whatever the day would bring.

A few years before his retirement he and Gillian bought Fennywood Farm near Winsford. It was their home for more than three decades. They had a small number of cows, endless hens and part-time sheep. At one stage they had a lady who helped Gillian in the house called Anne Card. She had two stock phrases for anything that she found unusual. One was ‘It’s funny, really’ and the other was ‘it’s amazing what they can do nowadays’. One day the AI man came to deal with Peter’s heifers. Mrs Card asked him what the man was there to do and Peter began to explain that rather than having a bull on the farm, the cows would be artificially inseminated. As he was explaining the process as euphemistically as possible, he suddenly got the giggles, wondering which of the expressions she would employ. She rewarded him with a somewhat quizzical ‘it’s funny, really.’

He ran the 40-acre farm in conjunction with the land in North Wales he had bought from his grandfather, Willie Irvine, in the early 1960s. He never tired of telling the story of how Willie had purchased the land as a grouse shoot for his sons, Alec and Tur, and of how his grandfather had grown to love that area of North Wales between Corwen and Bala. Creini, as Peter’s land was known, comprised three farms, a lake and a mountain. He loved that place more than anywhere else on earth. We used to take the caravan to Creini for our summer holidays. Gillian and any number of children, cousins and friends slept in the caravan and awning but Peter always preferred to sleep in a tent some way from our noisy camp. One morning we woke to see his tent entirely surrounded by inquisitive cows.

In 1977 he employed the 17-year-old son of a neighbouring farmer to run Creini for him. Arwel Griffiths worked as Peter’s farm manager for over forty years. Together they learned how best to run the land and maintain the integrity of its unique loveliness. In the early 1980s he decided to learn Welsh and over the course of several summers he attended Coleg Harlech for total immersion in the language. He became proficient and could conduct business successfully in both English and Welsh.

For years sheep would be sent down to Fennywood to overwinter. Peter and Gillian spent many springs lambing up to 150 sheep in the barns there. He would keep lists of every lamb that was born on either farm. Recently he was going through his papers and uncovered a handwritten list of sheep from 1978. All carefully numbered in his meticulous hand, each column ruled with a straight line. He wrote slowly and carefully, making sure every letter in his signature was the right height and shape. As he got older his handwriting slowed down and it once took him 45 minutes to write a cheque.

Peter loved to count. He would note the number of posts and rails along a field edge. He calculated the difference in the number of minutes over the course of a calendar year between daylight and night-time. He had an astonishing eye for detail and, for most of his life, an extraordinary memory. When a few years ago he heard that the Rachmaninoff third piano concerto was about to be performed he hummed the first two bars and said ‘gosh, that’s not often played. I last heard it in 1954.’

Music was another part of his life that he shared with us children in his own way. His grand piano was in the drawing room at Delamere directly below my bed. We all remember him practising at night after supper and we listened while we drifted off to sleep as he played a Chopin nocturne or a Beethoven sonata. His love of opera, Wagner in particular, was elegantly balanced against his passion for the 1970s TV series, Dallas and later, Blind Date with Cilla Black.

As you have heard from Christopher, Peter was a regular church goer for all of his life. He loved the rhythm of the church calendar but was wary of new-fangled ideas and modern hymns. He often read the lesson with clear enunciation and measured speed. A good public speaker, he was a member of the 25 Club, a debating society on the Wirral, for over sixty years. I believe he was its longest serving member.

I cannot end without referring once more to his nicknames, the most affectionate and appropriate of which came not from his immediate family but from his nieces and nephews: Uncle Speeds. Peter did not move fast in comparison to Gillian and that gave rise to the nickname. He also had one habit which anyone who ever had supper at Fennywood will recognise. Towards the end of the evening, he would grab the table edge, half raise himself, and announce: ‘Right, I’m going to bed’. All conversation would stop and those around the table would wait expectantly for him to rise and take his leave. More often than not he would sit back down on his chair and the evening would continue. Then the process would be repeated, sometimes three or four times. One evening Erica Toosey, who was living at Fennywood, got so infuriated with him that she picked up a tea cosy, which was shaped like a hen, and put it onto his head. ‘Uncle Speeds, will you please go to bed!’ She exclaimed. If he did, history does not relate, but the habit continued until well past his 90th birthday.

At the end of his life Peter was afflicted with Alzheimer’s. This cruel disease robbed him of his memory and us of the pleasure of his witty company. He had for as long as we can remember been able to deliver the mot juste for any occasion. When Tim visited him in hospital the day before we eventually sprang him out and brought him home, he said, in answer to the question of ‘how have you been Dad?’

‘I’ve been all over Europe, casting an ever-diminishing shadow.’ He came home on a Friday a few weeks ago and was surrounded by love and care, thanks to the marvellous Lydia Rose team who have been looking after him and Gillian since 2020. He died quietly, peacefully on Tuesday 15th February with Gillian and me at his side. That diminishing shadow has now disappeared but the memories of Peter John Summers, Uncle Speeds, Dad, FIL, Grandpa, Great Grandpa will be around for a very, very long time.

Dearest Julie, that was lovely. I’m so pleased you published it. So sorry to have missed the service, but at that point could hardly stand up. Hugh rang & told me he’d been over & that he’d seen lots of Irvines. I will write to your Ma, love Cxx

Thank you Christina and I’m only so sorry you couldn’t be there. It was lovely to see Hugh. Julie x

Dear Julie, So glad you have allowed this eulogy to be shown to all of us. Your father was a remarkable man . It is so interesting to read about his various exploits, so many I was aware of but knew little about. He will be sadly missed by a great many but especially by you and your family. My heart and sympathy goes out to you and we send much love particularly to your dear mother. Auriol and Family.

Thank you, Auriol. It was a great privilege to be able to share Dad’s remarkable life beyond the Thanksgiving Service. He was such a character and he is already sorely missed. I’ll certainly send my mother your love. Julie

A small correction: it was the Leas (not Lees) School at Hoylake, now demolished. My father went there before going on to Shrewsbury, where I was at Severn Hill later, overlapping with your father’s youngest brother. Another pupil at The Leas was Nicholas Monsarrat.