The strange thing about writing a book is that it starts as a germ of an idea and ends by being a public object. It is a bit like having a baby who grows into a child and then is suddenly thrust out into the world entirely alone to be loved or hated without protection from the parent (me).

When I first had the idea for Our Uninvited Guests it was a completely different creation in my mind. My son Richard and I were in Harrogate in 2012. We had been looking at Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries in the north east because I had been asked by the Commission to write panels to explain why there were large groups of CWGC graves in civilian or military cemeteries in this country. It is a little known fact that there are 13,000 Commission burial plots and cemeteries in Britain. But that is an aside. We were staying near the Hotel Majestic where, I was given to believe, my great-grandfather, Harry Summers, had spent the last ten years of his life. In fact, it turned out he had not lived at the Majestic but at the Prince of Wales Hotel. However I only discovered that last year. My interest was piqued by the idea that all the grand hotels in this magnificent spa town were earmarked by the government for requisitioning in the event of war and that is indeed what happened. The Hotel Majestic was taken over by the RAF; the ballroom at the George Hotel housed the General Post Office and so on. It was said that had London been bombed flat, the government planned to move lock, stock and barrel to Harrogate.

When I first had the idea for Our Uninvited Guests it was a completely different creation in my mind. My son Richard and I were in Harrogate in 2012. We had been looking at Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries in the north east because I had been asked by the Commission to write panels to explain why there were large groups of CWGC graves in civilian or military cemeteries in this country. It is a little known fact that there are 13,000 Commission burial plots and cemeteries in Britain. But that is an aside. We were staying near the Hotel Majestic where, I was given to believe, my great-grandfather, Harry Summers, had spent the last ten years of his life. In fact, it turned out he had not lived at the Majestic but at the Prince of Wales Hotel. However I only discovered that last year. My interest was piqued by the idea that all the grand hotels in this magnificent spa town were earmarked by the government for requisitioning in the event of war and that is indeed what happened. The Hotel Majestic was taken over by the RAF; the ballroom at the George Hotel housed the General Post Office and so on. It was said that had London been bombed flat, the government planned to move lock, stock and barrel to Harrogate.

So was born a book proposal entitled Hotel Majestic. The subtitle was always ‘the secret life of country houses 1939-45’. The more research I did the more I realised that it was the people and their lives in these houses rather than the houses themselves that interested me. Of course it is interesting to know that the government decided, in 1938, that any house with more than four rooms downstairs could be requisitioned under the Defence of the Realm Act. My house would have escaped but my sister’s would not, for example. So yes, the obvious places such as Bletchley Park, Woburn Abbey, Chatsworth, Blenheim Palace were taken over but so were smaller properties all over the country. In St John’s Wood a house with a garden that led straight onto Primrose Hill was commandeered by the Air Raid Precautions Unit while a small manor house in Sussex was used as a safe-house for French Resistance couriers en route to France.

So was born a book proposal entitled Hotel Majestic. The subtitle was always ‘the secret life of country houses 1939-45’. The more research I did the more I realised that it was the people and their lives in these houses rather than the houses themselves that interested me. Of course it is interesting to know that the government decided, in 1938, that any house with more than four rooms downstairs could be requisitioned under the Defence of the Realm Act. My house would have escaped but my sister’s would not, for example. So yes, the obvious places such as Bletchley Park, Woburn Abbey, Chatsworth, Blenheim Palace were taken over but so were smaller properties all over the country. In St John’s Wood a house with a garden that led straight onto Primrose Hill was commandeered by the Air Raid Precautions Unit while a small manor house in Sussex was used as a safe-house for French Resistance couriers en route to France.

Further, I discovered that the Ministries of Information, Food, Supply, War etc could take over any building they wanted almost anywhere in the country with barely a shrug. Greater Malvern became infested with civil servants, BBC employees and later Radar technicians. The one thing in that town in short supply was school boys. They had been ousted and were living at Blenheim Palace.

In Aylesbury, for example, no fewer than 60 properties were requisitioned in whole or in part. Sometimes the Ministry of Food forcibly commandeered freezers from ice-cream parlours, refrigerated plants and garages. At other times they took over tracts of land for access. The armed forces had almost carte blanche to occupy whatever they required.

A chaotic picture began to emerge and I soon realised that government bureaucracy, while fascinating for a page or two at most, is actually a killer. The book soon gained a new title: Behind Closed Doors. This very nearly stuck but there are a number of books and films with that name and the publishers decided in the end it should change to something more focused on the people rather than the houses. People matter: they are endlessly fascinating and almost always surprising when placed in unusual juxtapositions. BBC employees with beards cycling around the West Midlands are far more evocative than Nissen huts in Tewkesbury. Nuns in purple habits walking through the wild countryside near Bridgnorth captured my imagination as did an American journalist crawling over the heather in Northern Scotland. Why was there a pregnant mother from the East End sleeping in a hospital bed in the Prince Regent’s suite in a country house in Hertfordshire and why was a forger living in Audley End? What were they doing there and how did they cope with being completely torn from the roots of their former lives?

This is the question at the heart of my new book Our Uninvited Guests. If you have time to read it you will meet some of the most beguiling characters imaginable. I have favourites but I won’t spoil it by telling you who they are. Suffice it to say that this book has been one of the most delightful and challenging I have ever written. It took longer than any other both to research and write but the rewards for me personally have been immense. I hope they translate into a rewarding read.

Our Uninvited Guests is published on 8 March 2018 by Simon & Schuster £20.00

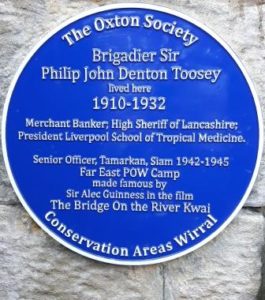

he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.

The two boats cross the line neck and neck. Then there is silence. The commentary ceases and the Finish Judge has to make his call. The wait seems interminable, time stands still. Then: The result of the Final of the Princess Elizabeth Challenge Cup was that Shr …. No need for the rest: the name of the winning crew is always announced first. The grandstand explodes in ecstasy … the verdict, one foot. More cheering. The narrowest, the shortest, the tiniest of winning margins imaginable, less than a sixtieth of the length of the boat.

The two boats cross the line neck and neck. Then there is silence. The commentary ceases and the Finish Judge has to make his call. The wait seems interminable, time stands still. Then: The result of the Final of the Princess Elizabeth Challenge Cup was that Shr …. No need for the rest: the name of the winning crew is always announced first. The grandstand explodes in ecstasy … the verdict, one foot. More cheering. The narrowest, the shortest, the tiniest of winning margins imaginable, less than a sixtieth of the length of the boat.