I was going to post this blog on 4 August after I had handed in the finished draft of my biography of Audrey Withers to my editor, Iain MacGregor, on 31 July, as per contract. However, on 25 April Iain asked whether I could bring the deadline forward by six weeks and deliver by mid-June. It is the kind of question that focuses an author’s mind in a way almost no other can. I agreed to have a go. My feelings on the way back from London that afternoon ranged from blind panic to the thrill of the challenge. Over the last six weeks I have gone from one to the other on a daily, sometimes hourly basis. But I met my deadline and delivered the book last Friday, a week before Iain was expecting it. That surprised even me.

The main reason it was possible to do what seemed almost unthinkable on the morning after my meeting with Iain was because I was able to clear the decks and my diary thanks to the support of my incredibly kind and understanding husband, Chris. He retired last year and was able to act as gatekeeper and cook so that all I had to do was to work. Sometimes that work involved thinking and puzzling over some knotty little problem or other so I did that while working in the garden or walking on the riverbank with the dogs or on my cycle ride to the library. But in the main I sat in my office, staring at a screen, thumbing through my notebooks with an exasperated ‘where the hell did I make a note of that?’ or looking out of the window at the sun-kissed garden wondering when it would rain.

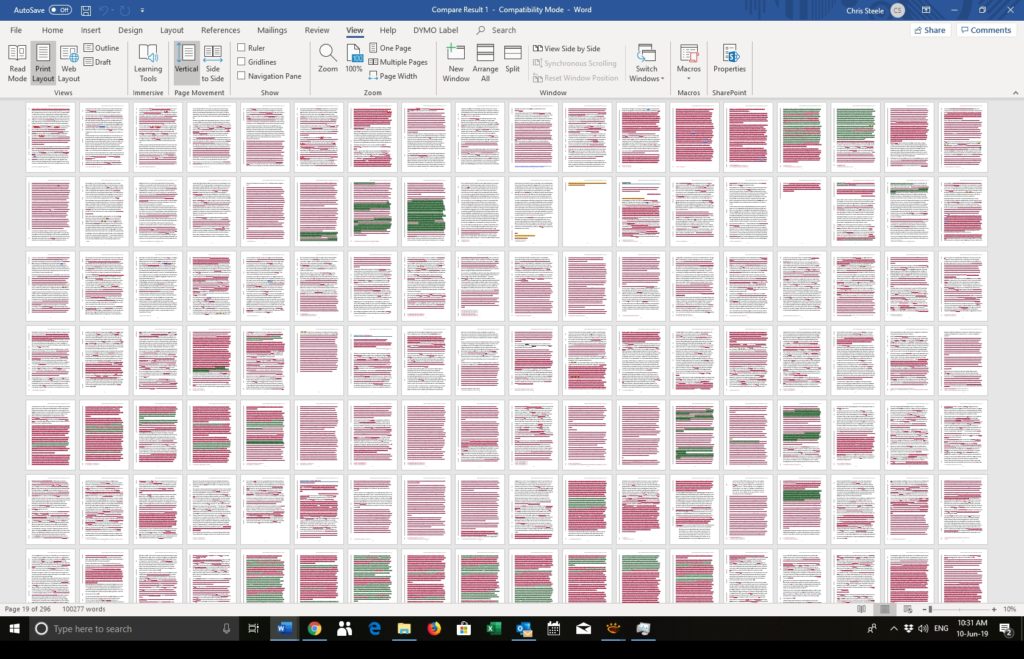

This morning we did a cross comparison of the difference between draft one of Audrey and the final version which is at least draft seven. Here it is.

As you will see from the amount of red on the screen, not much of the brilliant first plan survived contact with the editing enemy. I was astonished, to be honest. I had not realised just how much I had changed in the last two months (I had started editing before my critical meeting with Iain).

When I finished the first draft, I had the weekend off, then sat down on Monday morning and read the whole book through from cover to cover and tried to get a feeling for the overall story. That took three days and by the end I realized I had got a book that could work and although it was in need of a great deal of editing, it was at least a narrative. The next time I read it was for facts. Had I got everything in that I wanted to include, such as the vital memos or the story of her first marriage or her relationship with Lee Miller? That took two weeks and involved me using both my screens, one for the draft and the other to double check my electronic files. That is when a lot of changes took place and I needed a couple of visits to Vogue House to check issues of Vogue from the nineteen fifties.

The third read-through was for cadence. It seems a funny word to use but it is the best one I can come up with. Every chapter has to have a certain type of pace. Audrey once described how the readers of Vogue had to be led through the magazine page by page and there should be no ugly juxtaposition of stories. She was once very critical of a piece in American Vogue shortly after the war which featured luxurious clothes in Rome opposite a photograph of a starving child. For a book it is sometimes helpful to be able to change the pace and go from a piece of high action or drama of, say, war reporting, to a completely different type of event, such as a family funeral. For it to work it has to be deliberately but carefully done. I want my readers to feel some emotion. I once got ticked off by a WI lady who accused me of making her cry several times when she was reading Stranger in the House and she was rather put out when I said I was sorry but very pleased too. It is a sad book, telling some terrible stories about the impact on women of men returning from the war. Good that she was moved, good that she cried. I cried when I was writing some of those stories. War is a terrible thing and it has a long, long tail. A psychologist from Germany once said to me: ‘Hitler wanted the Third Reich to last for a thousand years. He didn’t succeed but the fallout from his experiment will last for generations.’

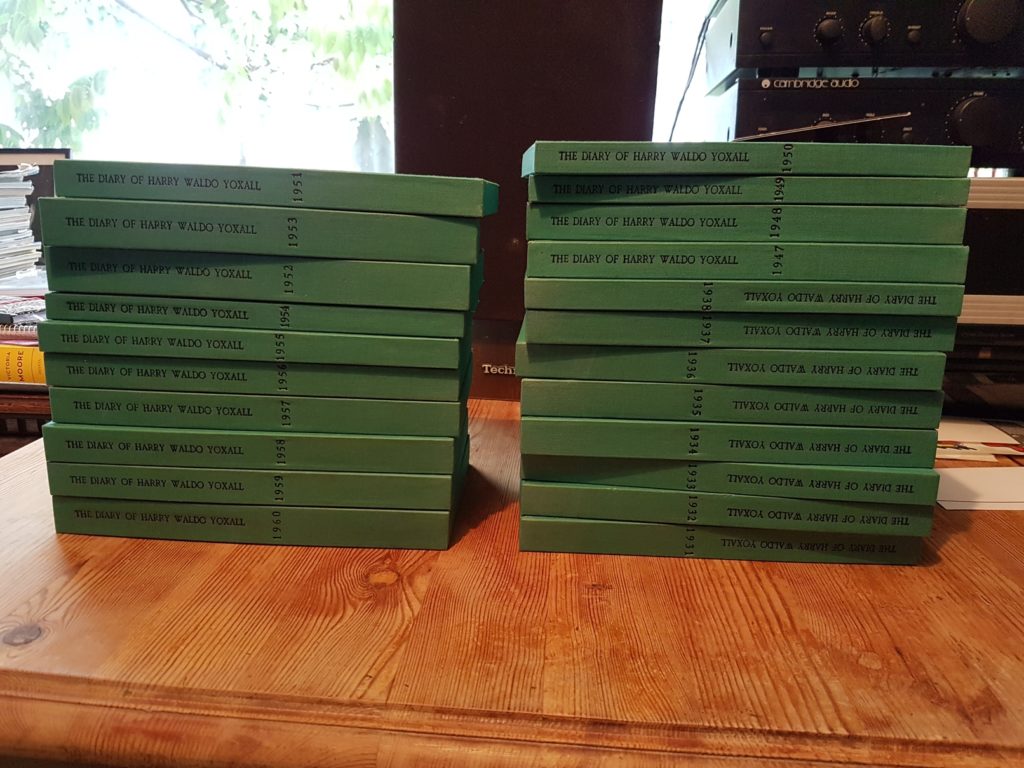

By the time draft three was completed I had had my meeting with Iain and the pressure was on. It was fortunate that I had got to where I was in the editing process because I could see how it would be possible to accelerate the next iterations. I think Audrey has benefitted from very close and energetic attention because I was forced to keep up a cracking pace and it meant that any research I still needed to do had to justify the time spent on it. I had one fantastic day in May reading the diaries of Harry Yoxall, Condé Nast’s managing director in the UK. He wrote about 250 pages a year and had the pages stapled and bound in slip cases with the year on the spine.

I had read the Second World War years at his great-grandson’s house in Surrey but the rest of the diaries were with his grandson in Suffolk. I needed to read the years Audrey was at Vogue, so 1931 to 1938 and 1946 to 1960. Twenty-two years or 5,500 pages or, even more scarily, 1,375,000 words. How the hell was I going to manage that in ten hours? In the end I worked out a way to scan his handwriting for Audrey’s name. He had quite a distinctive way of writing A and it made it relatively easy to find mentions of her. Less easy when the diaries were in French, which half of them were! Sometimes he typed letters to his wife and then used them as diary pages. They were a joy, especially the one from March 1953 when he attended an investiture at Buckingham Palace the day Audrey was given her OBE by a very young and nervous Queen Elizabeth. He was worried that the knighting sword was so heavy she might chop off the head of one of her subjects. That was a great discovery, as was the moment when I found out for sure that Audrey had left Vogue of her own volition and had not been gently asked to leave, which is what I and others had assumed. She told him over lunch in June 1957 that she intended to retire at the end of the decade. The trip was more than worth the day and a half it took to get there and back.

There have been other finds too, in the bowels of the Law Library in Oxford and in the microfiche copies of the Daily Sketch at the British Library but this blog is already too long…

So that has been the process and I plodded, raced, panicked, wept, laughed my way through the next weeks as I beat and bashed my writing into some sort of shape which I hope Iain will be able to work with. The next months are crucial as Audrey will be edited, copy-edited, proof-read, fact-checked and finally sent to the indexers prior to printing in the autumn. I have no idea how many more changes will be made but I expect quite a few. I am both excited and exhausted, but most of all relieved that I made it.

What a wonderful insight into the process this is Julie…i’m exhausted just reading it and, although I know you’re a seasoned writer, incredibly impressed with your work rate! Thank you so much for sharing it. I hope you can have a bit of a rest this summer…one legacy of the curtailed deadline maybe…

I so look forward to ‘meeting ‘ Audrey and finding out about her and her world x

Thank you Rachel. I might get a little bit of R&R this summer but there is still a lot of work to do.x

Wow! Aside from the mammoth task of creating narrative from such diverse resources, then transforming SEVEN drafts into your final version, you met the six-week-earlier challenge. Where do you get your energy from? (surely not all from Diet Coke?!) I look forward to seeing the result in print. Thank you for sharing your journey with us. x

Thank you, Ann. Nerves, that’s where the energy came from!! And I think it helps that I’ve been there before and know how to keep the pressure on myself and when to let up and take a breather. But it’s been hard and I’m not rushing to take on another book project just yet.