Audrey and Lee

In September 1944 Vogue’s editor, Audrey Withers, published a four-page spread with two turns at the back of the magazine on a field hospital in France. It was not the first time that she had brought her readers face to face with the horrors of war, but it was the most powerful reminder to date of the scale of the operations of D-Day. On 6 June that year almost 7,000 ships and landing craft had transported 156,000 infantrymen to the beaches of Normandy. Over the next weeks a further 2,500,000 would land on the coast of France to continue the push towards Berlin and the elimination of the Nazi threat. It was natural that newspaper and magazine editors would be following the story closely. But was it plausible that a glossy fashion magazine would want to take its readers into the heart of the war? After all, Vogue’s main fare was couture and culture, was it not?

British Vogue was called into being in the middle of the previous war. It was first published in London in September 1916, during the Battle of the Somme. Its pages were filled not only with fashion and features but also with articles on the war, including reports from Belgium on the plight of pregnant women giving birth close to the front line and the work of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry in France. By 1939 Vogue was 23 years older and had gathered experience and influence. It was not surprising that in this new war the editor would want to help readers make sense of what was happening at home and abroad. During the Blitz, Audrey Withers, included a photograph of Vogue’s bomb-damaged offices and proudly told readers that the magazine, like its fellow Londoners, was being put to bed in a cellar. This was a reference to the cellar below No 1 New Bond Street where the Vogue staff retreated during the nightly air raids and where they carried on working as if it were entirely normal.

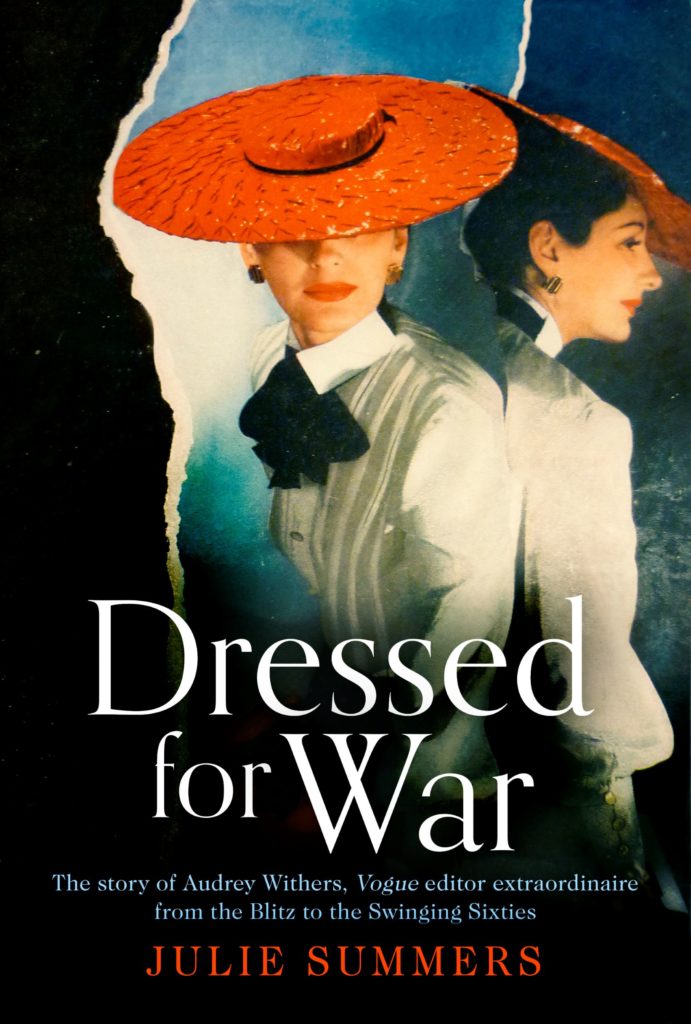

Audrey Withers once described herself as an unlikely editor of Vogue and this comment stuck to her reputation for the next sixty years. In fact, she was an outstanding editor. She was brave, single-minded and always alive to the most important matters of the day for her readership. At 5’ 10” in her stocking feet she was tall for a woman of the time. She had been brought up in an eccentric household where from a very young age she had been invited to engage with her father’s literary and artistic friends. One of these was the artist, Paul Nash, with whom she conducted a 16-year correspondence in which she tried out all her ideas about the world on him, often eliciting affectionate and amusing responses. It was Nash who advised her on attending Somerville College, Oxford and who applauded her decision to switch from English to PPE in her second term. And it was Nash who comforted her when she was awarded a 2.1 and not a First as she had hoped. When she decided to leave her first job in a bookshop and apply to Vogue, it was Nash who congratulated her on the appointment.

Audrey started as a subeditor, the lowliest job in the magazine, in 1931, and gradually rose through managing editor to Editor in September 1940. Her greatest champion when she made the step up to the top job was Condé Nast himself. He wrote to Harry Yoxall, the managing director of Condé Nast Publications in London, to say he would rather ‘have an editor who can edit than an editor who can mix with society.’ She may not have had the right social connections, but she had the intelligence and courage to stand up to the most difficult of Vogue contributors. She once took on Edward Molyneux who threatened to pull his advertisements if he did not have control over which photographs she used in the magazine She refused. Vogue's independence was more important to her than Molyneux's contribution to the magazine. Her wartime Vogue is a remarkable body of work that deals with all aspects of war, from clothes rationing and austerity, through the roles women took on both in civilian life and in the armed forces to the great battles being fought abroad. Her main photographer, Cecil Beaton, was removed to India and China in 1942 and she wrote ruefully of how much his absence would mean to her readers. However, another photographer was waiting in the wings, and this was Lee Miller.

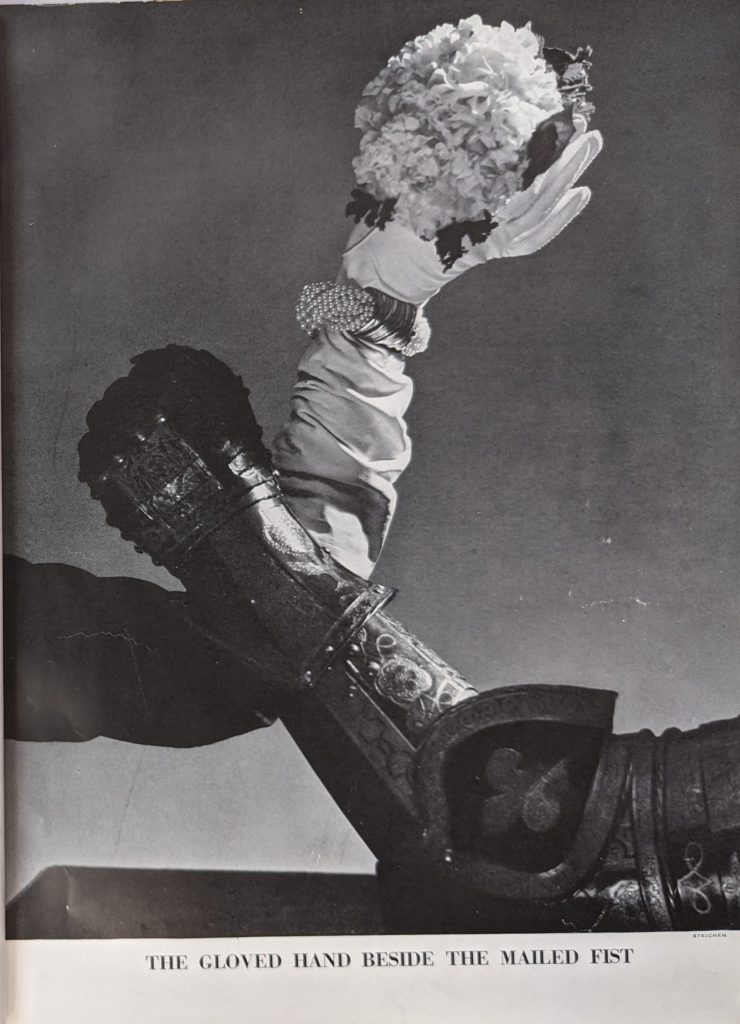

Lee had begun her career in the 1920s as a model, appearing on the front cover of American Vogue in 1927. She was described as one of the most beautiful women in the world. Her life changed when she went to live in Paris in the early 1930s where she worked as Man Ray's assistant. By the outbreak of the Second World War she had become a photographer with an exceptional eye and a singular ability to pick out the essence in a scene. This was to develop over the course of the Second World War. She arrived in London soon after the outbreak of war and applied to work for Vogue photographic studios in 1940. She worked as a fashion photographer for the magazine but also worked alongside features editor, Lesley Blanch, taking photographs of work done by the female armed services personnel.

The opportunity to get into France – occupied France – was only possible because of her US citizenship and the press accreditation Audrey had helped to secure at the end of 1942. Lee’s visit to the field hospital in Normandy in August 1944 left her deeply moved. Her photographs are fresh, absorbing and searingly honest, as is her writing: ‘Another ambulance arrived from the right and litters were swiftly transferred to the parlour floor. The wounded were not “knights in shining armour” but dirty, dishevelled, stricken figures … uncomprehending. They arrived from the front-line Battalion Aid Station in lightly laid on field dressings, tourniquets, blood-soaked slings … some exhausted and lifeless.’ Audrey was delighted with Lee’s work. She wrote later:

‘I made myself solely responsible for editing Lee’s precious articles. I used to begin by cutting whole paragraphs, then whole sentences, finally individual words. One by one to get it down. Always I tried to cut them in such a way that there would be the least possible loss of their impact. It was a painful business because it was all so good.’

What was new here, in Vogue, was the quality not only of the photographs but also of the writing. Combined it made some of the most powerful photojournalism of Vogue’s war. Today Lee Miller is well-known. When Audrey Withers agreed to sponsor her application for press accreditation there was little to suppose this would turn out to be an extraordinary relationship. Audrey later described it as the greatest journalistic experience of her war.

In October Lee had two features in Vogue, one on the battle for St Malo, where she had witnessed the use of Napalm, and the other from liberated Paris. She went on to produce articles on Operation Nordwind, a German offensive in Alsace, and then on the liberation of countries such as Liechtenstein. Her work became ever more intense as the war reached its conclusion. In April she entered the gates of Buchenwald and, just 12 hours after it was liberated, the concentration camp at Dachau. The photographs she sent back to London were so powerful and shocking that she sent an accompanying telegram ‘I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THAT THIS IS TRUE’. Audrey wrote that she had no difficulty in believing it was true: ‘The difficulty was, and still is, in trying to understand how it was possible for such horrors to be perpetrated not just in a fit of rage but systematically and carefully organised over years. To me, it was far more frightening than the existence of a Hitler or a Stalin and the fact that their crimes could not have been carried out without the willing cooperation of thousands who applied to work for the gulags and concentration camps just as if it was a job like any other.’

Audrey’s courage failed her. She could not bring herself to publish the photographs from Buchenwald and Dachau in her Victory issue of the magazine in June 1945. History, and she herself, has judged her harshly for that but both overlook the fact that she included Lee’s article in full. And the article is so packed with rage it almost burns the pages it was published on:

‘My fine Baedeker tour of Germany includes many such places as Buchenwald which were not mentioned in my 1913 edition, and if there is a later one, I doubt if they were mentioned there, either, because no one in Germany has ever heard of a concentration camp, and I guess they didn’t want any tourist business either. Visitors took one- way tickets only, in any case, and if they lived long enough they had plenty of time to learn the places of interest, both historic and modern, by personal and practical experimentation. . . Much had already been cleared up by that time, that is, there were no warm bodies lying around, and all those likely to drop dead were in hospital. Everyone had had a meal or two and were being sick in consequence – because of shrunk stomachs and emotion. There is a diet arranged for them now, very similar to what they have been receiving in texture, although the soup now contains vegetables and meat extracts. I had seen what they had, that emergency day; and you’d hesitate to put it in your pig bucket.

The 600 bodies stacked in the courtyard of the crematorium because they had run out of coal the last five days had been carted away until only a hundred were left; and the splotches of death from a wooden potato masher had been washed, because the place had to be disinfected; and the bodies on the whipping stalls were dummies instead of almost dead men who could feel but not react.’

As Audrey was a wordsmith, she knew the power of Lee’s words and I think it is telling that she chose not to tone down the fury that they conveyed.

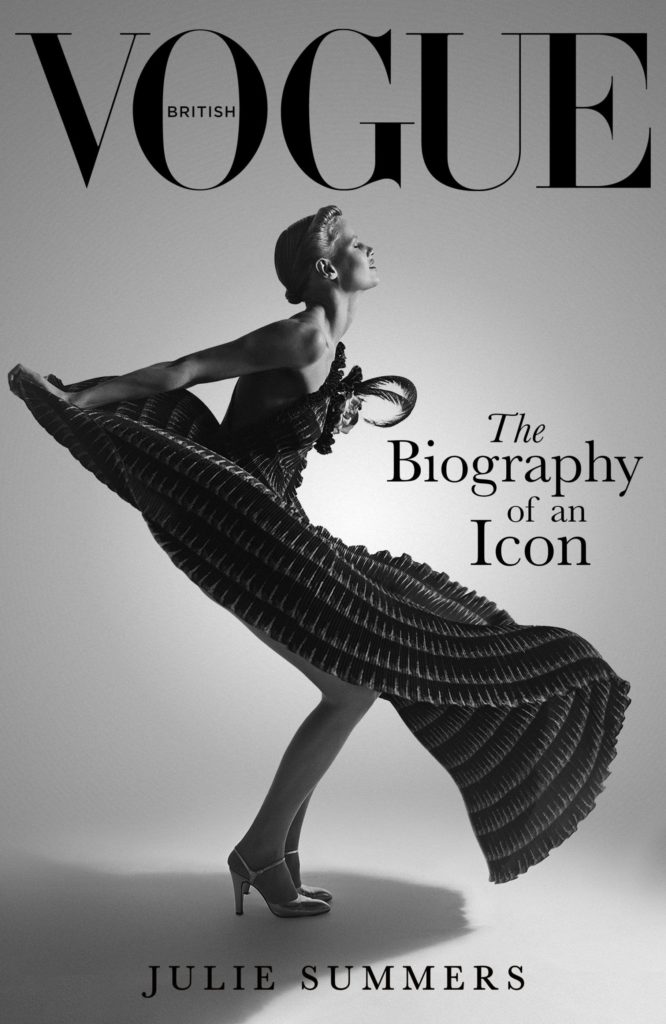

The current film LEE, which is enjoying success worldwide, with Kate Winslet as Lee and Andrea Riseborough at Audrey, naturally focuses on Lee and her war photography. I just want to remind readers that without Audrey Withers, Lee’s work might never have gained the prominence in Vogue that it did. Lee was extraordinarily brave and brilliant but so too was her editor.

With thanks to the Lee Miller Archives for the use of two images www.leemiller.co.uk