On Saturday 8 June 2024 over 600 people gathered at the Royal Geographical Society in London to mark the 100th anniversary of the disappearance of George Mallory and Sandy Irvine. Among the crowd were more than 30 members of the Mallory family, 8 Irvines and a good showing of Odells, Nortons, Somervells and Morshead (from the 1922 expedition). It was a great event and one charged with more emotion than I had expected.

It all started with a reception for the family members where at least sixty of us gathered in the entrance hall. It was fun to renew friendships and meet other expedition party relatives. It is not often you can walk up to someone and ask boldly ‘so, who are you?’ and get a friendly response of ‘I’m a Norton/Somervell/Odell.’ Meantime a film made by the Alpine Club, Everest Revisited 1924-2024, which looks at the 1920s Everest expeditions, was premiered in the lecture theatre. It focuses on all the participants, including the sherpa and porters, as well as the two well-known protagonists. It offers a fascinating mixture of archive footage, interviews including Chris Bonington, Stephen Venables, Dawson Stellfox, and Leo Houlding in Mallory replica clothing, and thought-provoking commentary from Ed Douglas comparing the 1920s expeditions with today.

Leo Houlding, Graham Hoyland and I each gave a short illustrated talk to shed light on various aspects of the 1924 expedition. Leo talked about making the IMAX film The Wildest Dream on Everest in 2007. He remembered Conrad Anker calling him out of the blue in 2006 and asking him how he would like to play Sandy Irvine. ‘The easiest decision of my life’, he told us. Filming is a lengthy process and no more so than for IMAX which requires huge cameras, batteries and other gear, and a lot of hanging around as shots are set up. Tedious at the best of times but dangerous on Everest. Seeing the footage of him hugging his toes in a tent after standing out in the snow and wind at some bewilderingly high altitude brought home the intensity of the cold on the mountain. His description of climbing the second step without the use of the Chinese ladder was particularly fascinating to the eager experts in the audience. He summited late in the season – on 14 June 2007 – so the IMAX team could be assured of an empty summit.

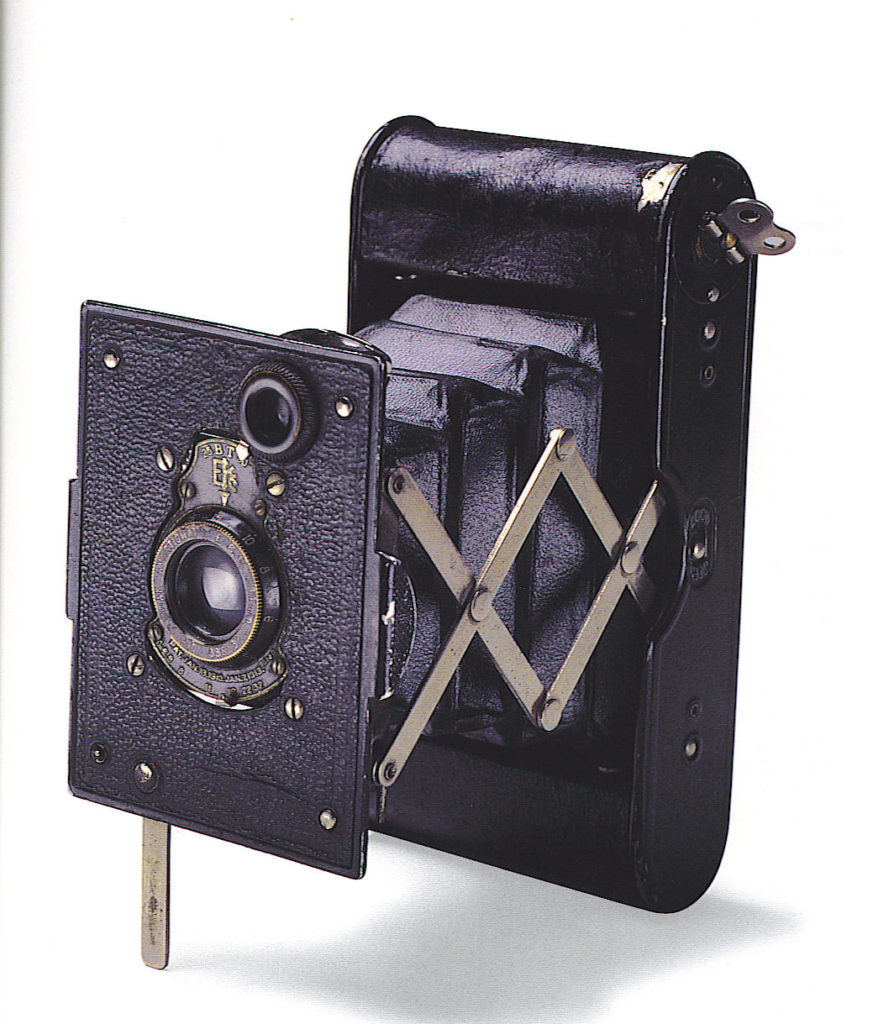

Graham led us into the story of his relative, Howard Somervell, who famously gave George Mallory his Kodak Vestpocket camera as he prepared to leave Camp IV with Sandy Irvine for the final summit bid. The question of whether, if the camera is ever found, there will be a film to be developed has continued to fascinate Graham – and tens of thousands of others. What he also brought to our attention were Somervell’s notes on barometric pressure on Everest which proved that the pressure was as low on 8/9 June 1924 as it was during the great storm of 1996 that killed so many climbers. Both Leo and Graham believe it is unlikely the two climbers made it to the summit, though not impossible.

I took the audience back to Sandy’s childhood so that they could get some sort of picture of the man who has always stood in Mallory’s shadow. When he wrote to his wife, Ruth, from the voyage to India, Mallory said of Sandy Irvine ‘he’ll be one to rely on for everything except, perhaps, conversation.’ This phrase has been quoted over the last 100 years to condemn poor Sandy Irvine as a slightly thick if very able sportsman. Nothing could be further from the truth, and I had fun talking about his wild childhood adventures, his engineering genius evident even at school and his great rowing prowess. I didn’t dwell on his love affairs as they have been well-covered, but believe me, he was active on all fronts.

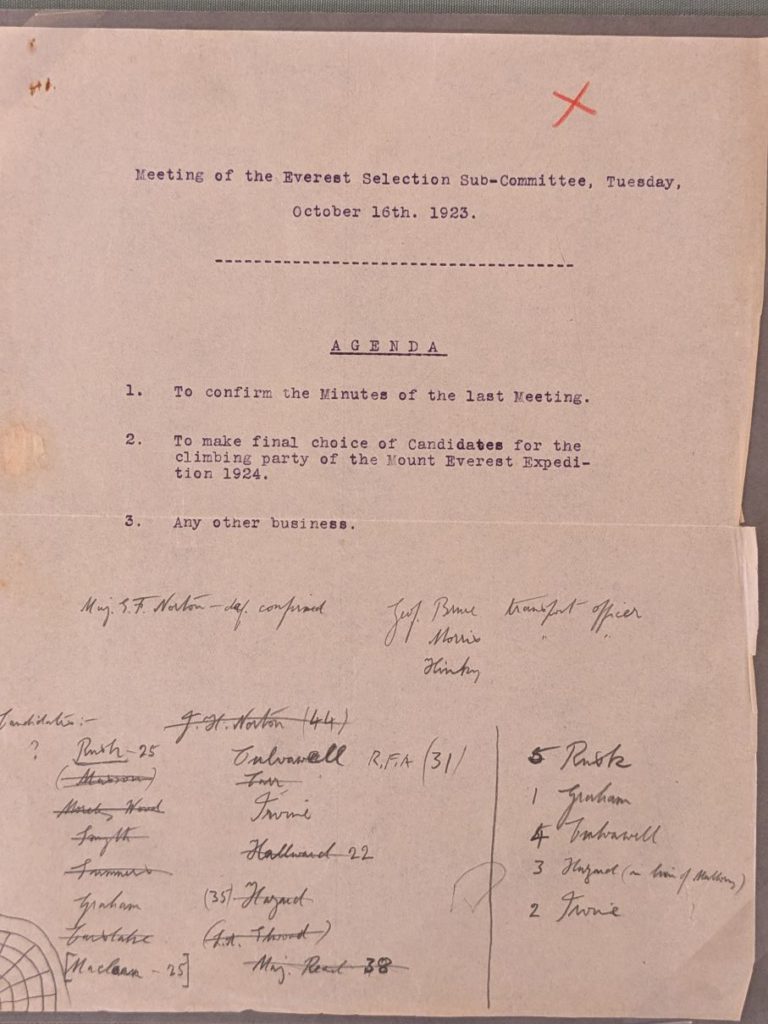

After the break Dr Wade Davis zoomed in from Vancouver to give us the most extraordinary and moving talk about the Everest team members from all 3 expeditions of the 1920s. All but a handful had been involved in the First World War. He talked movingly about how Dr Arthur Wakefield (doctor in 1922) had lost his faith after witnessing only 37 survivors of the more than 800 men from his regiment from Canada who were slaughtered on the first day of the Battle of the Somme; how Howard Somervell, on duty as a young surgeon that day, saw six acres of injured and dying men; how Colonel Edward Norton took part in almost every campaign in the War. It was a tour de force and at times it was almost too painful to contemplate what those men had witnessed. Wade is brilliant and he was able to offer light relief when discussing how the expedition members were chosen. George Finch was an Australian with a very colourful married life who was left out of 1921 on account of being off his food, tired and having lost weight (he was in the middle of a second, untidy divorce). He was allowed to go in 1922 and performed well but was dropped in 1924 with no reasonable explanation. Though this did leave a gap which was filled by Sandy Irvine. What came out of this talk was the humanity and bravery of the expedition members, but also the sadness of the loss of Mallory and Irvine. He quoted Edward Norton’s remarks at Base Camp in the aftermath: ‘We were a sad little party. We accepted the loss in that rational spirit which all of our generation had learnt in the Great War … but the tragedy was very near: our friends’ vacant tents and vacant places at table were a constant reminder to us.’

Norton wrote a letter to Sandy’s parents after their deaths, and I thought it would be fitting to quote from it at some length. I still find it moving today:

“Much that your son was to us I have already written of in various communiqués to the Times – From the word go he was a complete & absolute success in every way. He was spoken of by General Bruce in an early communiqué as our ‘experiment’ – I can assure you that his experimental stage was a short one as he almost at once became almost indispensable – It was not only that we leant on him for every conceivable mechanical requirement – it was more that we found we could trust his capacity, ingenuity & astonishingly ready good nature to be equal to any call. One of the wonderful things about him was how, though nearly 20 years younger than some of us, he took his place automatically without a hint of the gaucherie of youth, from the very start, as one of the most popular members of our mess.

The really trying times that we had throughout May at Camp III & the week he put in at Camp IV were the real test of his true metal – for such times inevitably betray a man’s weak points – & he proved conclusively & at once that he was good all through – I can hardly bear to think of him now as I last saw him (I was snowblind the following morning & never really saw him again) on the North Col – looking after us on our return from our climb – cooking for us, waiting on us, washing up the dishes, undoing our boots, paddling about in the snow, panting for breath (like the rest of us) & this at the end of a week of such work all performed with the most perfect good nature & cheerfulness.

Physically of course he was splendid – as strong as a horse – I saw him two or three times carry for some faltering porter heavier loads than any European has ever carried here before. He did the quickest time ever done between some of the stages up the glacier – one of his feats was to haul, with Somervell, a dozen or so porters loads up 150 feet of ice cliff on the way to the N. Col. As for his capacity as a mountaineer the fact that he was selected by Mallory to accompany him in the last & final attempt on the mountain speaks for itself.” As Norton himself said to Geoffrey Bruce when discussing Sandy Irvine, ‘men have had worse epitaphs.’

As we were marking the centenary in London, other commemorations were taking place around the country. In Birkenhead Dr Philip Walton put a candle in the window of 56 Park Road South, as Sandy’s mother had done in Wales when he disappeared. A light to show him the way home.

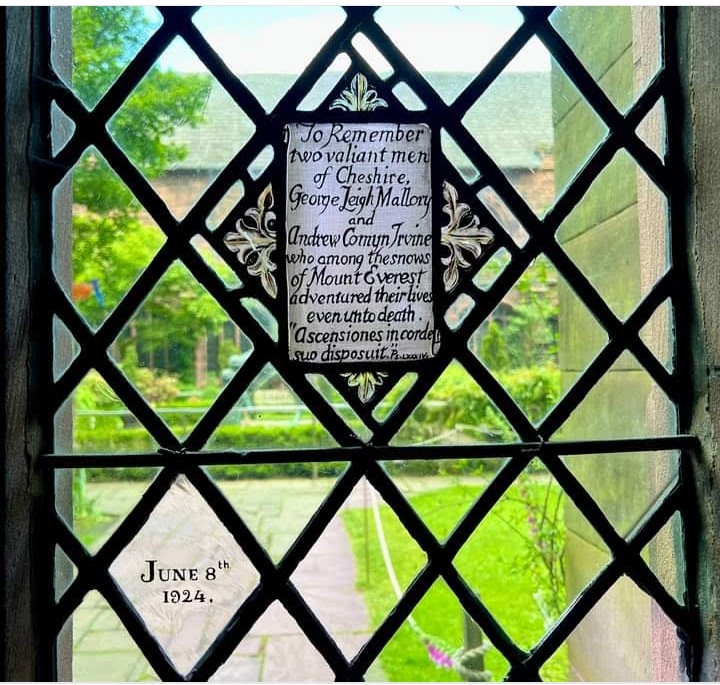

At Chester Cathedral’s evensong the choir and congregation processed to the stained-glass window in the cathedral’s cloisters dedicated to Mallory & Irvine. There they sang Psalm 121 and said prayers ‘in remembrance of their journey’.

Merton College flew the college flag at half-mast – a rare honour – and someone had laid flowers at the Irvine memorial in the college gardens. I had unveiled a blue plaque to Sandy Irvine on the wall of 56 Park Road South on Friday and the mayor of Birkenhead did the same for Mallory at 34 Slatey Road. It is extraordinary how this story of the disappearance of two men a century ago still touches people and moves them.

It has been a great journey and a huge joy to be involved in a quarter of a century of the Mallory and Irvine story. Now I am going to hand over to the next generation. I have loved getting to know great men and women from the world of mountaineering, including the wonderful Rebecca Stephens who led the event on Saturday on behalf of the Himalayan Trust. I am proud to call her a friend.

What can I say but thank you?

For anyone interested, there are exhibitions about Sandy Irvine and George Mallory at the following venues:

Merton College Oxford – see www.merton.ox.ac.uk for details

Birkenhead Park Visitor Centre https://birkenhead-park.org.uk/events/sandy-irvine-from-birkenhead-to-everest/

The Alpine Club, http://www.alpine-club.org.uk/events/past-future-exhibitions/1276-everest-1924

he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.