For the first six months of 2024, I was busy and taken up with two projects. The first was the centenary celebration of the disappearance of George Mallory and Sandy Irvine on Mount Everest on 8 June 1924. The second was the completion of my biography of British Vogue which was in the final stages of proofs, and we were looking to pin down the pictures. It was a delightful juxtaposition. I enjoyed flitting between exquisite photoshoots by Nick Knight and Mario Testino in Vogue and the chilly black, white and blue world of the high Himalaya. While the book proofs were being tweaked and the index completed, I took part in several events to mark the Everest 100th anniversary. The first was at Shrewsbury School in February, the day the expedition set off from Liverpool on 29 February 1924. Then a seminar day on 26 April at Merton College, Oxford (Sandy Irvine’s college) on the day he got his first sighting of the mountain from Pang La Pass 100 years ago.

And finally the major celebration at the Royal Geographical Society in London, organised by Rebecca Stephens and the Himalayan Trust. This took place on 8 June, the exact date the two climbers were last seen by Captain Noel Odell ‘going strong for the top.’ It was an extraordinary and moving event and we all felt that the centenary of the greatest mountaineering mystery of all time had been well and truly put to bed. I even announced my intention to retire from Everest-related matters.

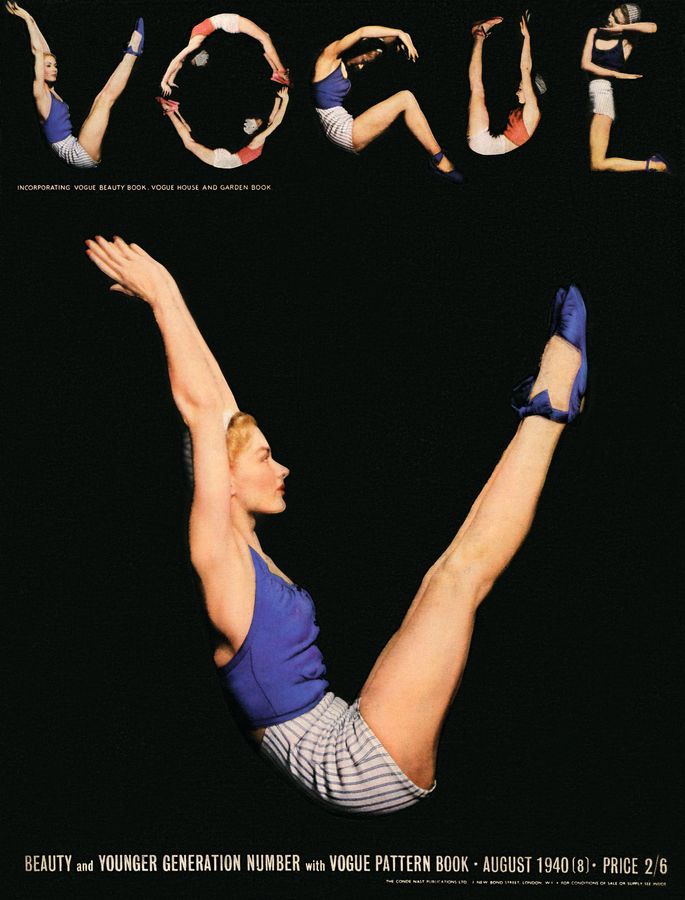

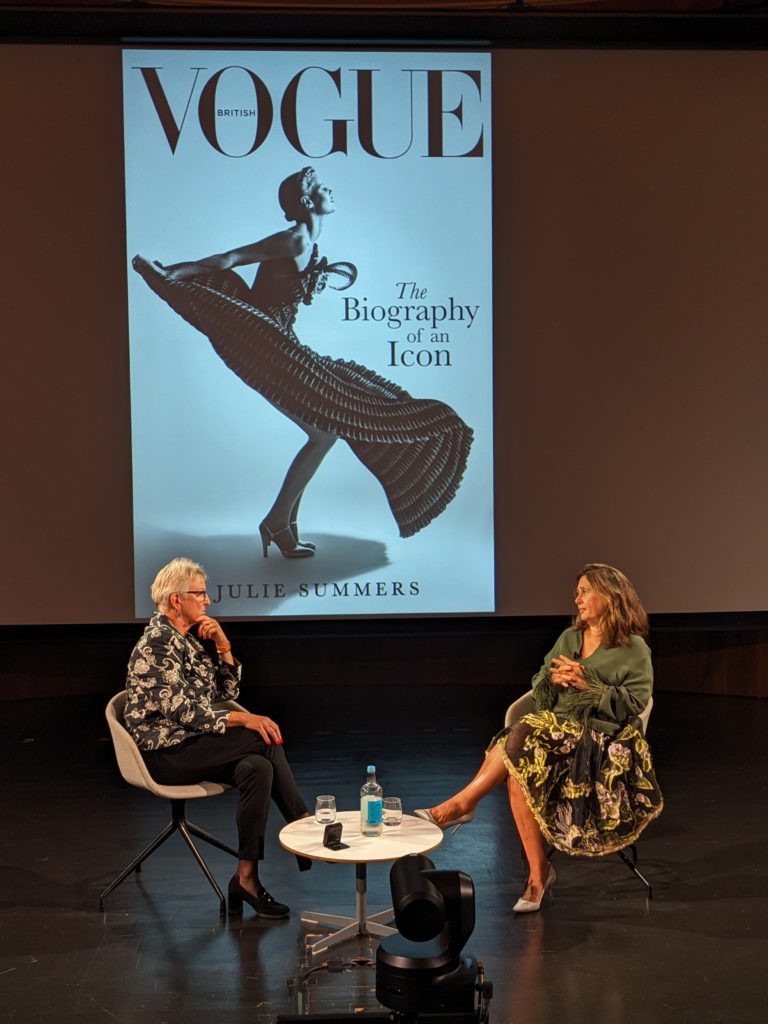

And so I returned to the rarified air of high fashion and Vogue history. Over the summer I finalised the selection of images for the plates section, saw the final proofs off to the setters and then, as readers of this blog will know, I was fortunate enough to see the book coming off the presses on 3 September. After a short but lovely walking holiday in Greece, I returned to a frenzy of pre-publication activity for the Vogue biography. There was a glitzy launch at Iconic Images Gallery in London and a Q&A with former Vogue editor, Alexandra Shulman at the V&A at which we discussed Vogue, clothes and other things that matter.

One of the issues we talked about was how all of us make fashion choices every day, even if we think we are not interested in fashion. We make a decision about whether it’s a jeans or dress day, whether it’s warm enough to wear shorts or a skirt without tights, whether we’re trying to dress to impress or simply to wear clothes appropriate for the task in hand. Our clothes tell others so much about who we are, what we are doing, and in the case of history, to what time period we belong. Audrey Withers, Vogue’s editor in the 1940s and 1950s, said she could date a dress to a season and tell you what was going on at the time politically and economically.

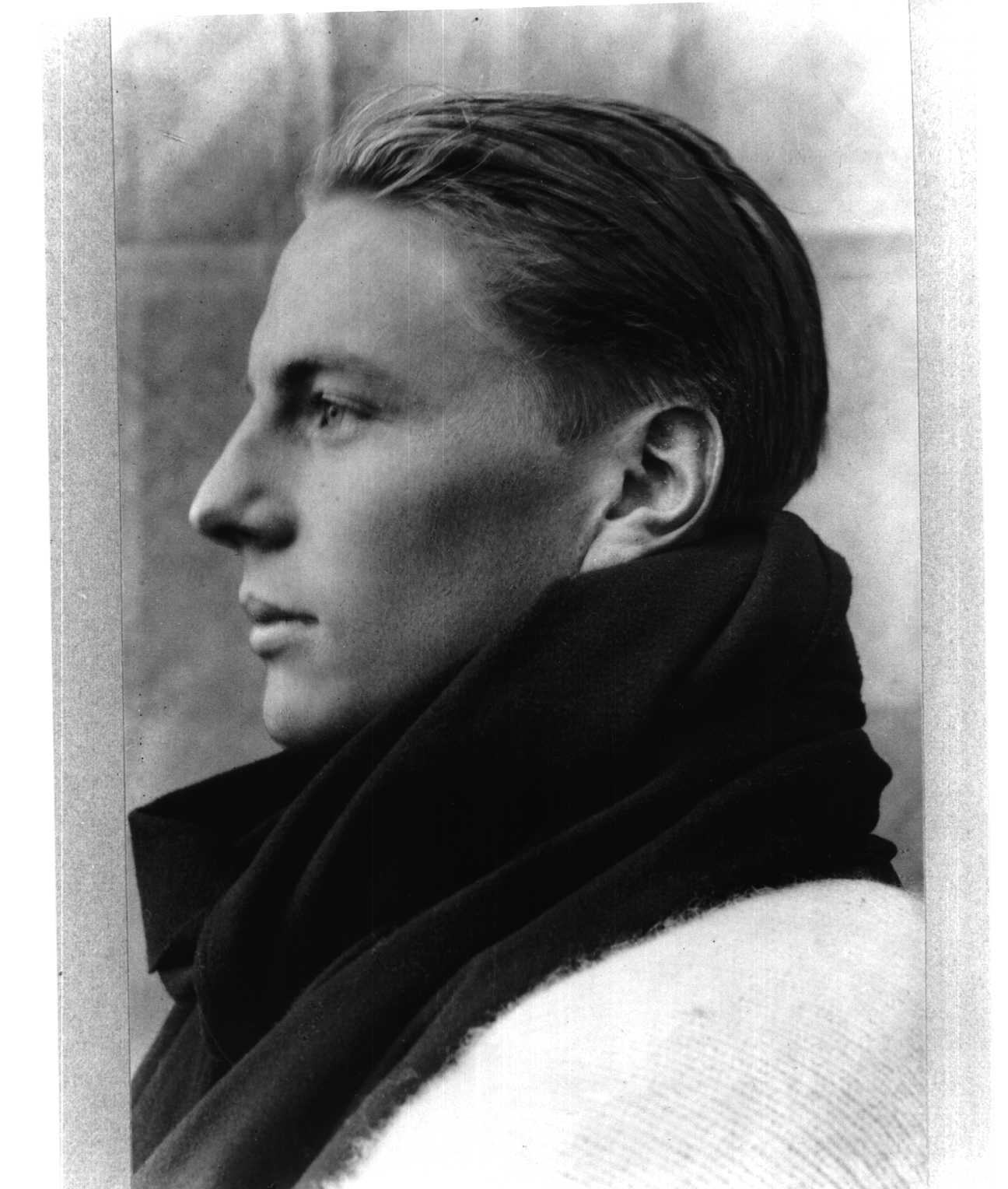

Imagine my surprise when I received a call one morning the following week from a high-altitude filmmaker in Kathmandu who wanted to talk about an old boot he had found in a glacier on Everest a few days earlier. The boot was leather with nails (for grip), meaning it had been used for climbing. There was a thick woollen sock poking out from the boot – brown and cream (café au lait?) which meant the wearer had been clear that he or she wanted to keep their feet warm at altitude. Actually, I knew it was a ‘he’ because no women were on Everest in the era of nailed leather boots. It matched in type, design and weight, the boot found on George Mallory’s body in 1999. Could it possibly be a boot belonging to Sandy Irvine? If so, that would blow all the most recent theories of the Chinese removing Irvine’s body from the mountain to smithereens. How could we possibly prove it? Simple, as it turns out. Stitched perfectly onto the sock was a Cash’s name tape: A. C. IRVINE.

This incredible find, made by climber/filmmaker Jimmy Chin when he was on his way down from the upper mountain, has opened up the whole mystery of Mallory and Irvine for the second time. And in the centenary year, a quarter of a century after Mallory’s body was found by Chin’s friend and mentor, Conrad Anker, in May 1999. The fact that Chin found only a boot and sock (with the foot too) is tantalising and begs the question as to what happened and where is the rest of Sandy Irvine’s body. I have studied the mystery of Mallory and Irvine for nearly 30 years, and I have spoken to many climbers, filmmakers, mountaineering historians, glaciologists and artists. I know that objects caught in glaciers are moved, crushed and spat out by the slow-moving rivers of ice. Andy Parkin, an artist in Chamonix, specialises in sculptures created from found and recycled objects, often crushed and changed by the Mont Blanc glacier. I knew from conversations with him how things can reappear years after they fell into the ice.

Those who know the story of Mallory and Irvine well are aware of the sighting of ‘an English Dead’ by a Chinese climber in the 1970s. The body, as he described it to a Japanese climber a decade later, was sitting upright, as if asleep, and was wearing old fashioned clothing, puttees and red braces. Mountaineering historians Audrey Salkeld and Thomas Holzel concluded this could only be Sandy Irvine. They set off to find out if that was indeed the case, but their search was not successful. When Eric Simonson’s Anglo-American expedition set off in 1999 to search for Irvine’s body they contacted my father, Peter, and asked for a DNA sample so they could identify the remains if they found them. In the event, the climbers stumbled upon the remains of George Mallory. Photographs of his frozen body ricocheted around the globe and a whole new generation of Everest enthusiasts became hooked on the story.

One of those I spoke to frequently was Graham Hoyland, who was key to the 1999 expedition and is a relative of another member of the 1924 Everest team, Howard Somervell. In 2011 we were discussing yet another expedition planning to try to find Irvine’s body and he said: ‘I think it’s unlikely that they will find anything. There has been a lot of avalanche activity and probably landslides in the region of old camp VI. I reckon your great uncle will have been sluffed off the mountain and into the glacier.’ I distinctly recall that word sluffed. Since then, other expeditions have tried to find Sandy Irvine’s remains and all have failed. One recent expedition leader, Mark Synott, has gone on record to allege that the Chinese had taken Sandy Irvine’s body off the mountain. In the Daily Mail in April 2024 he is quoted: ‘We now have multiple sources all essentially saying the same thing: the Chinese found Irvine, removed the body, and are jealously guarding this information from the rest of the world – all to protect the claim that the 1960 Chinese team was the first to reach the summit…’

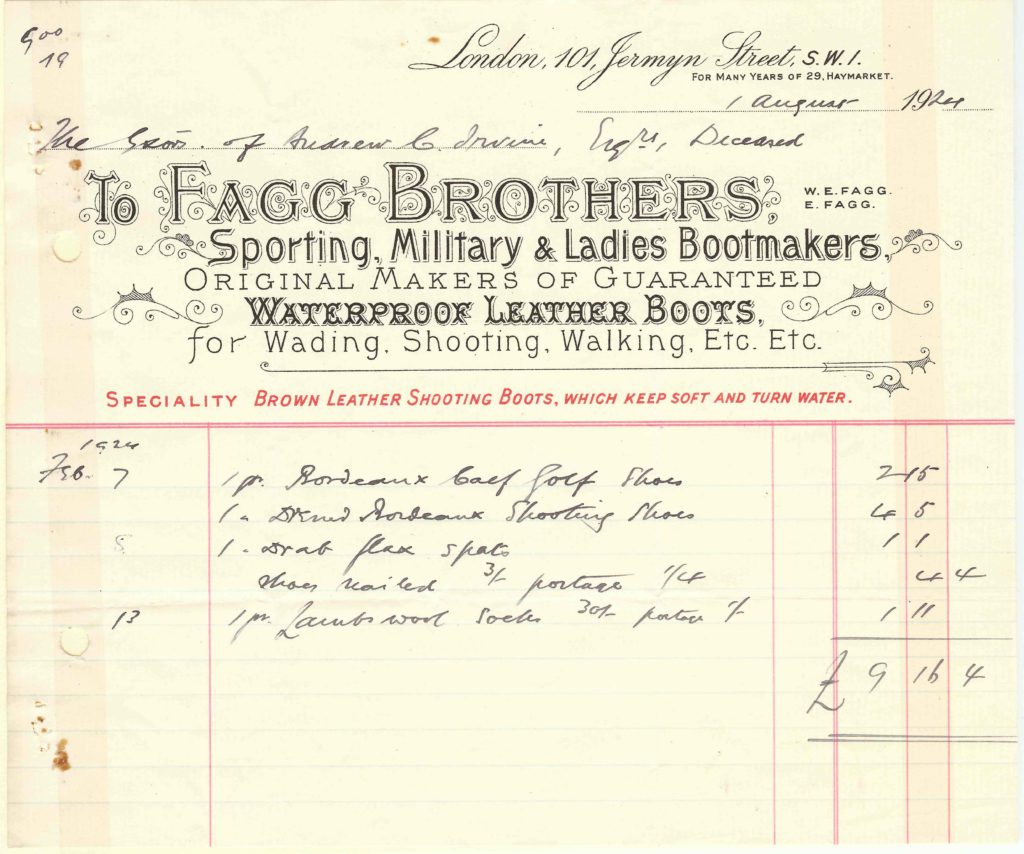

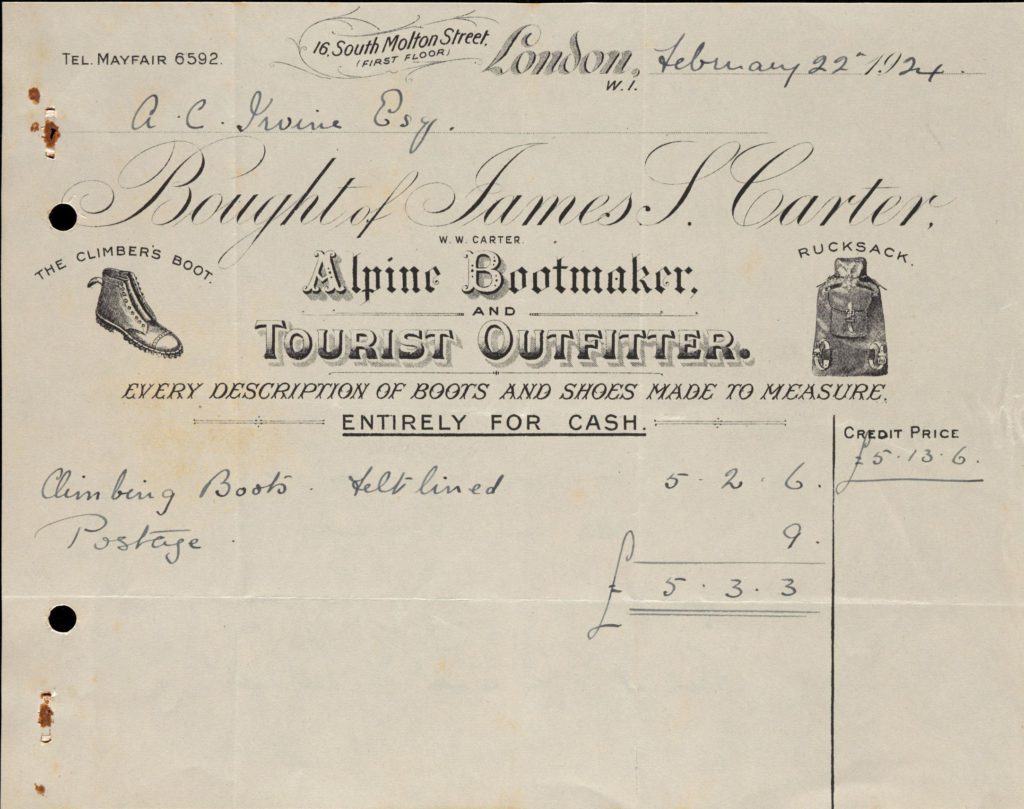

Well, that’s one theory that is well and truly put to bed now. Sandy Irvine’s body was never removed from Everest. That the boot is his, there is no doubt, thanks to the name label on the sock. And just for fun, the invoices for both the boot and the lambswool socks are in the archive of Merton College, Oxford. There is even a photograph of Sandy drying his socks at Shekar Dzong in the collection of the Royal Geographical Society. Sometimes history comes together beautifully, like a perfectly knitted woollen. And it turns out that clothes do matter.

These two images courtesy Sandy Irvine Archive, The Warden and Fellows of Merton College, Oxford