British Vogue: The Biography of an Icon Part 3 The Cover Story

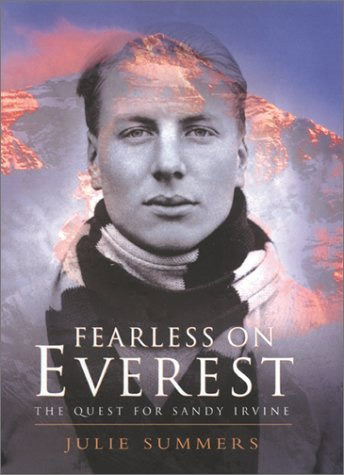

This blog is the story of the jacket of my Vogue biography. The name ‘jacket’ raised quizzical smiles in the archives at Vogue House when I mentioned it. The immediate response of the archivists was to imagine Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent or Dior, while I was thinking about how on earth to sum up the content of this survey of a century in one image. Book covers matter, whatever the old adage might tell you. Some authors are so devoted to their designer that they will countenance no one else to touch their book jackets, or in the case of paperbacks, book covers. It is their brand. For my books, given the range of dates and subjects, it has been a one at a time process. I could not, for example, have the same sort of cover for this book as I did for a book about the Bridge on the River Kwai or Mount Everest.

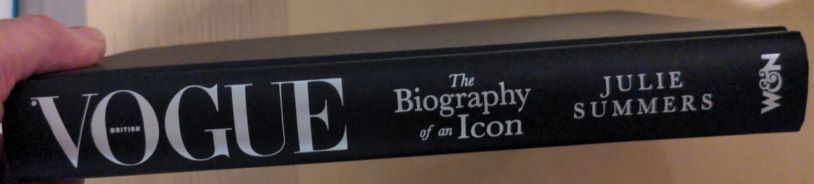

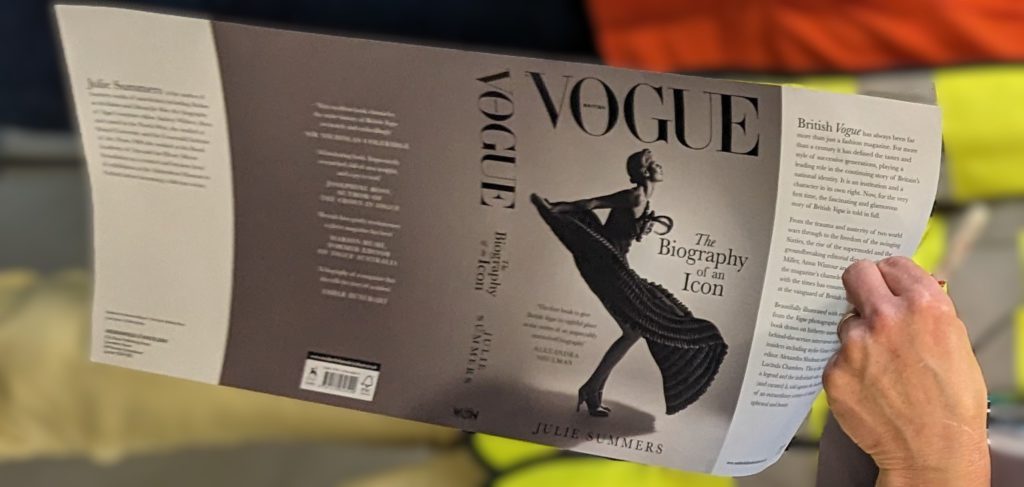

Book production, like everything else, has its own language and is incomprehensible to most outside the industry. Books have cases, covers and jackets. The first thing one sees after printing is the uncased version, which is simply the book’s pages. It is a white block and looks wholly uninteresting (except to the author). It is then put in a case, which is a hard cardboard sheet that is creased in the middle to provide what will become the spine. It usually has the name of the book and the author on that spine. In my case, the black case was embossed with the title in silver. And then there is the jacket, which is the shiny, thick paper that wraps around the book and makes it stand out on the bookshelves of shops, supermarkets, airport stores and anywhere else the publisher plans to make it available for sale.

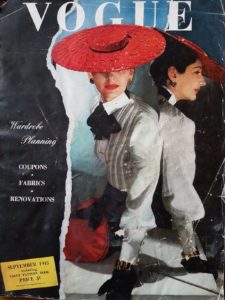

The hunt for an image started in July 2023 when Maddy Price, my editor at Orion, sent through a couple of suggestions. Neither worked. It seemed to us that any image we might pick from the remarkable collection of fashion shoots over the last 108 years would date the book to a decade, and for some eagle-eyed aficionados, to a year or month. We had a conversation about it and decided that the only thing to do was to plump for a single, bold, plain colour with the title in gold or silver. It was not a wholly satisfactory solution, so we parked it for the while. Maddy got on with editing my manuscript and I went to France for a holiday.

I had met the photographer, Willie Christie, in December 2022 when he came to Oxford, and I interviewed about his time at Vogue in the 1970s. He had a brief but productive spell as a Vogue photographer, working with Grace Coddington who was then the fashion editor. He showed me a selection of photographs that were to be included in his book, due out the following year. ‘You should come to the launch’, he suggested. On 20 September 2023 that is exactly where I was to be found: at Iconic Images Gallery in London, admiring a small selection of his beautiful photographs with my friend Deb. I was very taken by a black and white image of model singing into a microphone with a pianist in the background. It felt so Hollywood and timeless.

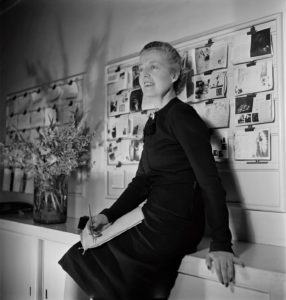

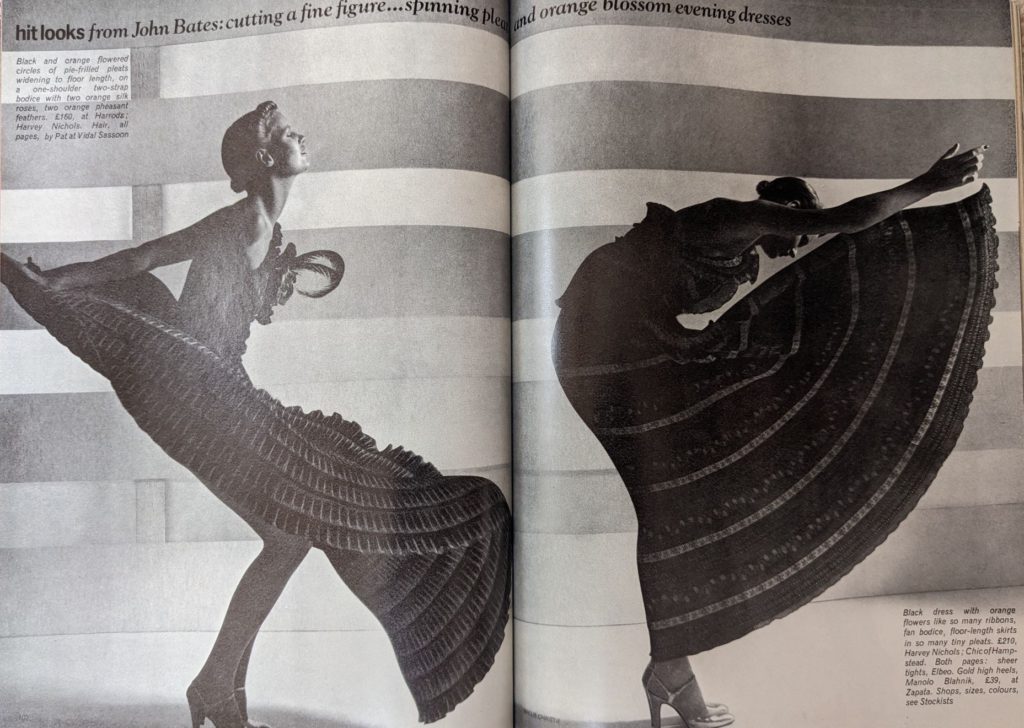

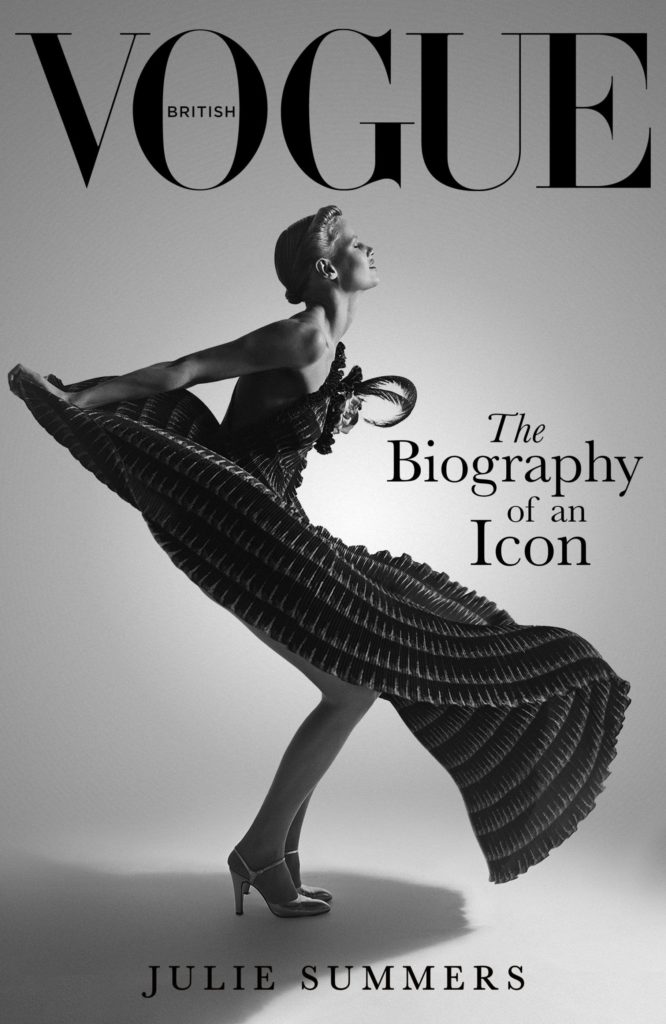

Deb bought me a copy of Willie Christie’s book which I read on the train on the way back to Oxford that evening. Turning page after page of stunning images my eye was caught by the shot of a model wearing a John Bates dress against a slatted background lit from behind. The more I stared at it, the more I realised I had found exactly what I was looking for: an image that was timeless, beautiful, spoke of luxury and desire but also of movement and life. Had I not spotted this when I was reading Vogue of the 1970s? As soon as I got home, I looked up the 15 March 1977 issue and there it was, on page 100. But a muddy version of this crisp and lovely image in Willie Christie’s book. I remember reading a memo by editor Beatrix Miller from around that time complaining about the quality of black and white reproduction in Vogue.

I sent a snap of the picture to Maddy Price the next morning and received an enthusiastic thumbs up. She passed it onto designer, Chevonne Elbourne, who mocked up a version of the jacket. The thing she realised was that she had to interpret Willie Christie’s image as a portrait shot, whereas his original was a square format, shot on a Hasselblad. With bated breath I forwarded her suggestion to Willie. Would he mind us messing around with his photograph? I knew he did not like his images to be cropped, but we had gone further and removed the slats. To my inexpressible delight he gave permission for us to use Chevonne’s design, and she was able to work on what has become the final version of the book’s jacket.

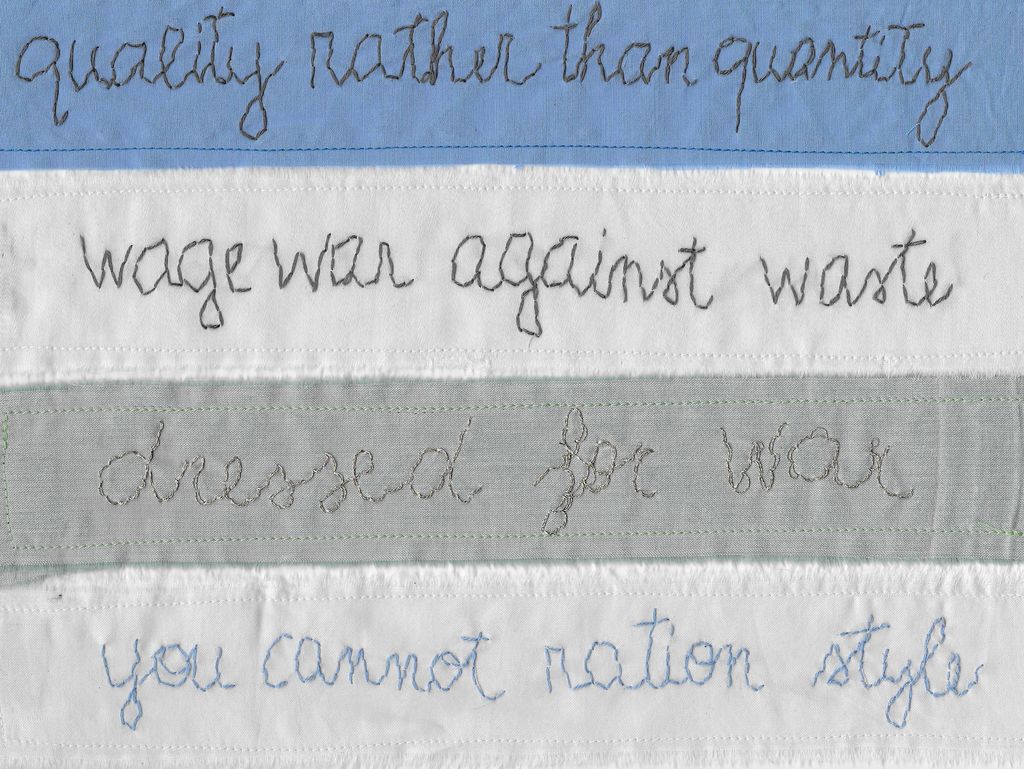

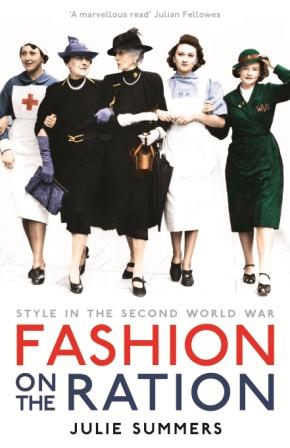

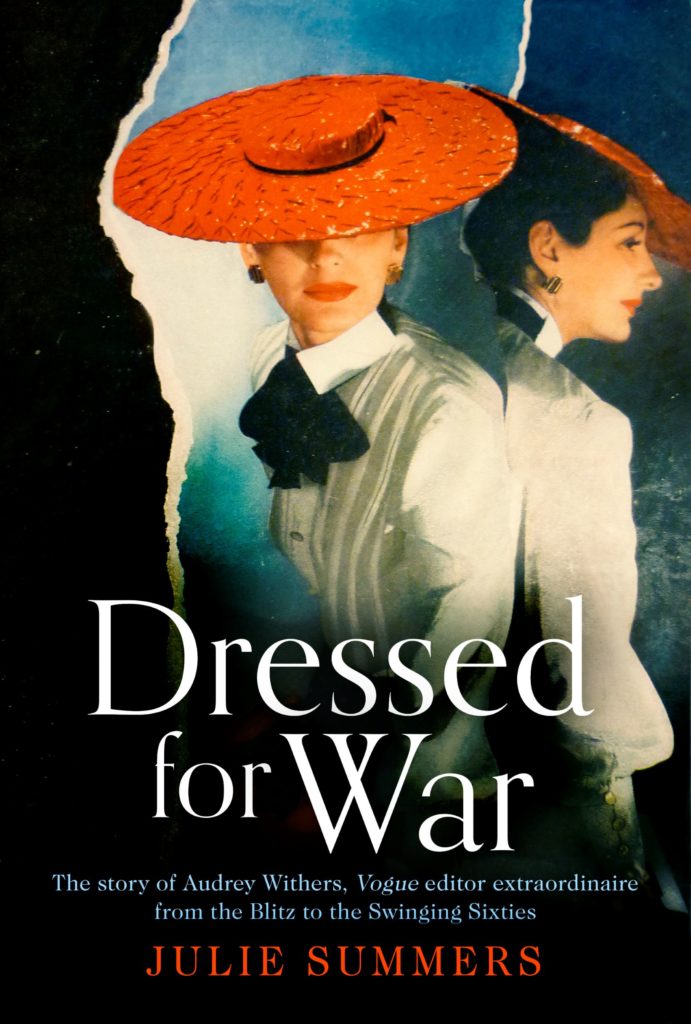

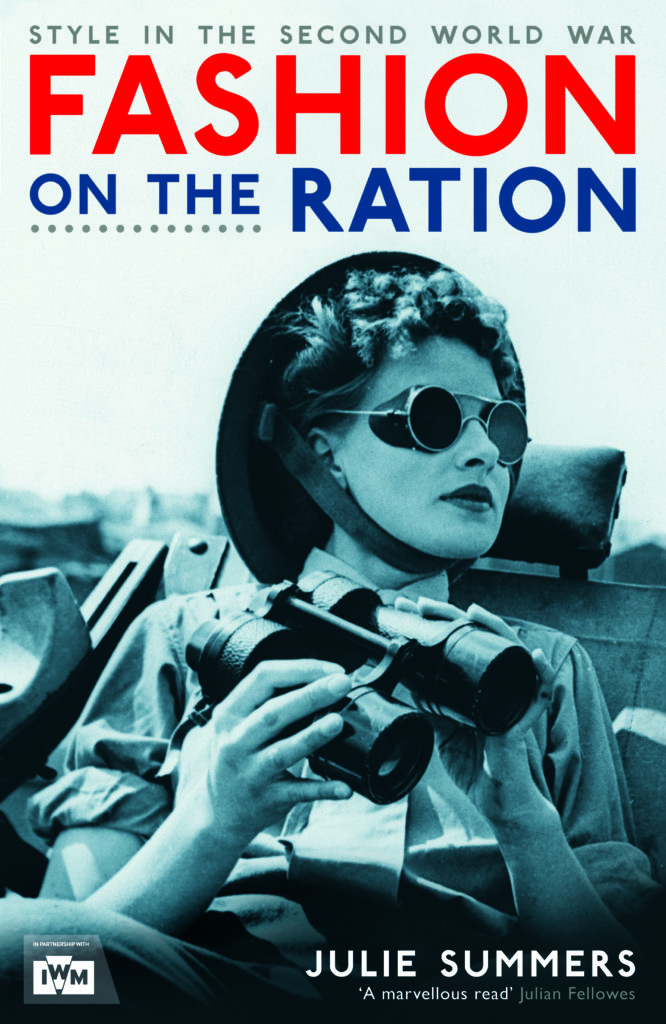

I now have most beautiful book jacket in my collection of cracking good jackets – Dressed for War, Fashion on the Ration and so forth. It is an image that conjures everything this book is about: luxury, beauty and style but also movement, life, energy and humour. If you chance to look beyond the cover, you will see Chevonne’s brilliant endpapers, which bring a blast of colour in the display of Vogue covers over the last 108 years. It is a very clever juxtaposition and I am in awe of her eye.

I would like to invite you to judge this book by its cover but beyond that, it is up to you whether you like my take on Vogue’s eye view of the 20th and 21st centuries. I owe a huge debt of thanks to Willie Christie for allowing us to interpret his glorious image from 1977 and to Chevonne Elbourne for working her magic on this and the other images from Condé Nast Publications that are included in the book.

My three favourite jackets to date in reverse order. Fashion on the Ration was published in 2015, Dressed for War in 2020 and British Vogue, the Biography of an Icon, in October 2024.