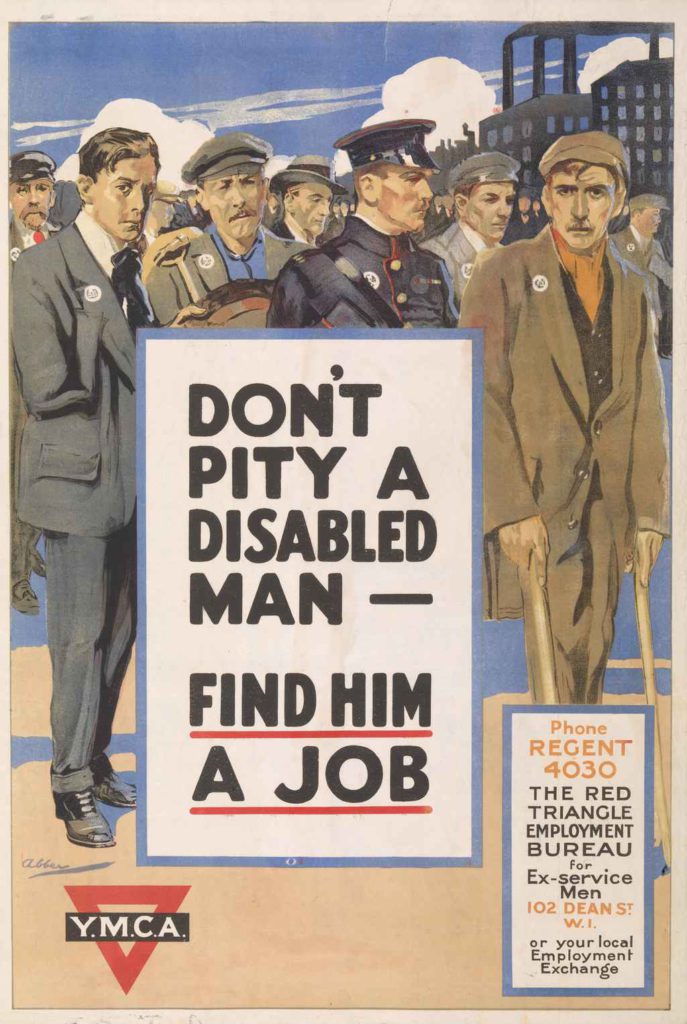

I mentioned in a previous blog that one of the things that struck me about the Royal British Legion was the age of its membership around the time of its formation. Rather like the Women’s Institute when it was set up in 1915 with its members average age of 24 years old, the Legion’s profile was young. Many of the men who had returned injured during and after the First World War were in their twenties. Some had missed out on education and apprenticeships as a result of conscription. What these men wanted more than handouts or sympathetic support was a job. The Legion was active in helping tens of thousands of men to find work after the war but there was a cohort of disabled men for whom it was much more difficult to find employment. Sometimes their disabilities meant they were physically unable to undertaken manual work. A man who had suffered a spinal injury or who had lost a limb would not be able to work in a factory or in agriculture, but he needed a job.

The Legion knew that nothing was more demoralising for a man who had returned injured to be told he could not work. It worked hard on many fronts but none more so than for these men. The Poppy Factory, one of the Legion’s best-known and popular undertakings helped thousands of men and families over the years offering employment and support. It still does. Poppy making is a year-round business and although the busiest period is in the run up to Remembrancetide, there is a permanent workforce at the factories in Richmond and Aylesford who keep the poppies and wreaths pouring off the production line.

A less well-known project is the car park attendant scheme. It may not strike you as the most exciting thing that you have ever heard of but bear with me. By the late 1920s the motor car had become a familiar sight on Britain’s road. Of the roughly 2 million vehicles in circulation, just under half were privately owned cars. That meant that people could take use their cars for leisure journeys, such as eating out, going to the cinema or shopping. A horrible side-effect of increased motoring was high road fatalities. In 1934 over 7,000 people were killed in car-related accidents, with pedestrians being half of the victims. Put into context, there were 38.7 million vehicles registered on Britain’s roads in 2019 and the road deaths totalled 1,870.

Some of the most dangerous places were town and city streets. With no official car parking in place, apart from in London, motorists simply left their cars where they wanted, regardless of how dangerous that might be to fellow road users and pedestrians. Councils realised that something had to be done and in 1927 the Rochdale South Branch of the Legion set the ball rolling. They agreed with the town council that in exchange for a rent-free piece of land they would employ two disabled men to run the first town car park. Rochdale Council let the Legion erect a hut and the two men, in attendants’ uniforms, manned the carpark on behalf of the town. This was so successful that it was repeated in towns and seaside resorts all over the country. It thrived after the Second World War and by 1960 the Car Park Attendants Scheme employed over 3,000 men. Today carparks are generally automated but spare a thought when you leave your vehicle in a little car park tucked away behind a municipal theatre or town market-place: it was probably first run by a disabled veteran supported by the Legion.

We all know about London taxi drivers whose knowledge of the metropolis within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross is so great that they are known to have a larger and more developed hippocampus than the rest of us mortal souls. Did you know, however, that at one stage a third of all London cabbies had been through the British Legion’s London Taxi School? I, for one, did not, so thought it worth exploring. The School opened its doors in 1928 and was available to ex-Servicemen. It was particularly popular amongst those with spinal injuries who could not stand for long periods or operate heavy machinery. The idea came from Lieutenant General Sir Edward Bethune who was a veteran of the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878-80, the First and Second Boer Wars, and the First World War. He believed that men who had learned to drive during the war would be suitable students. The scheme was supported by the Legion’s Honorary Treasurer, Sir Jack Brunel Cohen MP, who had lost both his legs in 1917. He and Sir Edward succeeded in getting Lord Nuffield to donate a taxi for training purposes.

The Taxi School was run by the Legion, who paid for a third of the costs, the remaining two thirds being covered by the government. The training was arduous, taking at least 12 months and often longer with men going out day after day, week after week, on bicycle or on foot, notebooks in hand, noting routes and “points” where taxis are usually picked up. Fred Marks, who completed the course in 1947, wrote about his experiences: ‘When at long last the Carriage Office is satisfied [with your knowledge] then comes your driving test – a stiff one. You are directed into a narrow back street and told to turn your cab around. A private motorist would do it in 20 movements, perhaps. You must do it in three.’ Remember, readers, this is pre-power steering, so not an easy feat. The Legion’s London Taxi School ran for 67 years. By the time it closed its doors in 1995 over 5,000 men had passed the famous Knowledge and the stringent driving test to become a London cab driver.

There is still a connection today. Any ex-Serviceman or woman who is scheduled to attend the National Service of Remembrance at the Cenotaph in London in November can hail a participating Poppy Cab at one of the agreed points around the capital and find him or herself transported there and back for free. The cost of this service is supported by the Legion, which gives the Taxi Charity for Military Veterans an annual grant. It is one of the most popular ways of helping veterans to get to and from the Cenotaph. The taxi drivers, some of whom had been through the Legion’s Taxi School, see it as a way to pay back part of the debt owed to the veterans old and young.

One way and another the Royal British Legion has helped to keep veterans on the move for over a century and in a way that we, the public, have all benefited from.